DOES KARATE WORK? - Iain Abernethy

A traditional art meets modern street violence. Are you one of the many karateka who have found yourself asking ‘why?’ when performing a kata? After practising a move from kata over and over to ‘perfect’ it, has it occurred to you that you still don’t know how to apply it in real combat?

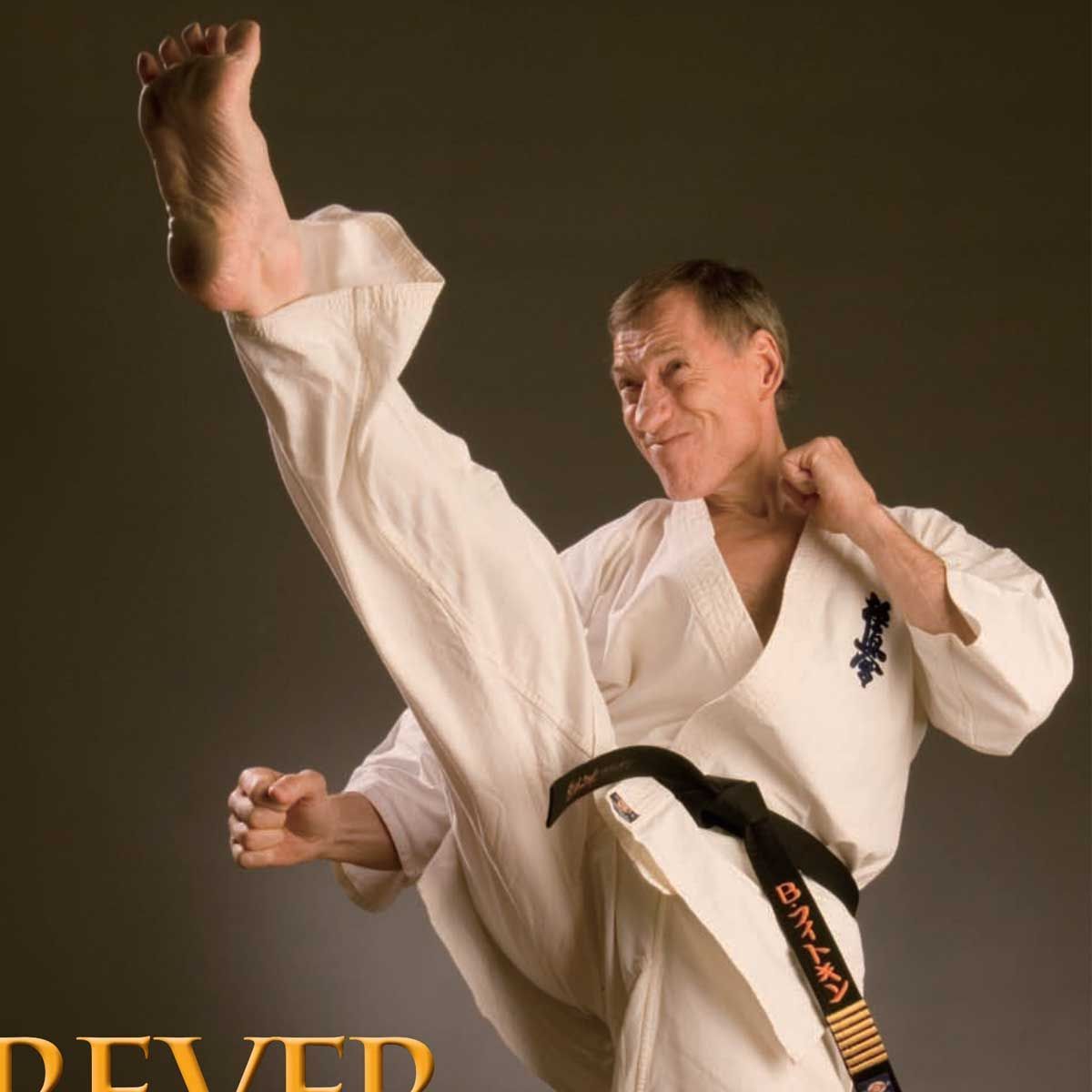

World-renowned Shotokan karate instructor Iain Abernethy has written a number of books and produced over 20 DVDs on the practical application of karate, and specialises in dealing with this common conundrum. Each year the England-based sensei travels extensively to teach seminars on the topic, and offers this insight prior to his visit to Melbourne next month.

STORY BY IAIN ABERNETHY

How relevant is karate to the needs of modern day self-protection? It’s fair to say that there are a growing number of martial artists who would question whether a traditional art like karate has any relevance to contemporary violence. However, as someone who has extensively studied both karate and modern reality-based self-defence systems, I see very little difference in the core combative methodologies of the two approaches. Karate lacks very little when trained and applied correctly.

Over the years, karate’s effectiveness has been diminished through an emphasis on form and aesthetics over function, which has meant that many modern karateka care more about how something looks than how effective it is. The failure of instructors to specifically identify the requirements of self-protection means that the needs of real fighting, competition, grading requirements, etc. all get lumped together, and thus karate students often don’t have a clear idea of what works in real situations. These problems are perhaps most clearly seen in the modern approach to kata. Kata was originally intended to be a way of memorizing and training highly effective techniques and tactics that were specifically created for civilian self-protection.

Today, however, the ‘shape’ and look of the kata has become more important than the information contained within the kata. The other main problem is that people now see a kata as being a choreographed ‘fight’ with other karateka, rather than a physical record of techniques and concepts that can be applied in real self-defence. Many karateka also don’t understand how the realities of self-protection differ from those of a fight with another karateka. The good news is that all of these issues can be easily addressed if we approach kata in the right way. Believe it or not, kata is the key to ensuring karate’s effectiveness in the modern world. It is within the kata that we fi nd the original art that is untainted by the requirements of karateka-vs-karateka competition.

I have nothing against competitive karate, but it’s important that we understand that the skills it develops and exhibits — while perfectly good in themselves — are largely inapplicable in the close-range, chaotic world of self-protection. It is to the kata we must look for effective selfprotection methods. I see kata practice as having four stages, and it is through the study of these four stages that we can fi nd just how effective karate can be.

The first stage is the practice of the solo form — this is what most people think of when they talk about kata practice. The first thing that a karateka learns is the actual physical sequence of the kata; the body mechanics required for maximum efficiency; the correct mental attitude, etc. This is a very important stage of kata practice. If you are unable to perform the movements of the form in an efficient way when there is no opponent present, you will have absolutely no chance of being able to make those same techniques work when an aggressive opponent is trying to cause you physical harm.

This initial stage of solo performance is often where kata practice begins and ends in many modern dojos. One of the main reasons for this is that the criteria used for determining the quality of a kata is frequently just its visual appearance. If the kata looks good, then it is good! This is obviously a fl awed way to view kata when you consider that kata is supposed to have a functional and pragmatic purpose. It is better to judge a kata against its pragmatic usefulness; if the karateka can successfully apply the techniques of the kata, then their kata is good, regardless of what it looks like. I’m not saying that poor solo performance is acceptable, just that the goal should always be function as opposed to appearance.

A functional kata will often be striking to the eye, but this is essentially an irrelevant by-product rather than the purpose of kata training. Gichin Funakoshi, the founder of Shotokan karate, wrote in his book Karate-Do Kyohan: “Once a form has been learned, it must be practised repeatedly until it can be applied in an emergency, for knowledge of just the sequence of a form in karate is useless.” Although the solo performance of a kata is very important, it should not be viewed as the entirety of kata practice. We need to be sure we progress our training onto the subsequent stages. The second stage of kata training is studying the functional application of the movements of the kata (bunkai). You need to practise applying the techniques of the kata with your training partners.

At this point, it’s worth pointing out the important distinction between realistic applications and the more common long-range, choreographed karateka-vs-karateka battles that are so often seen. Katas were not designed for fi ghting other karateka; they were intended to be a record of realistic techniques for use in a civilian environment. In real situations, attackers do not assume a stance and then execute an oi-zuki from 10 feet away! If we accept that kata were designed for use in real situations, then we must also accept that in a real situation we are very unlikely to face a fellow karateka, especially one who executes their techniques in such a contrived and formal manner (you can thank your lucky stars if you ever do). The applications of the kata should be simple, close-range and not dependant on the enemy performing certain actions in a certain way. Let’s look at the Pinan Godan/Heian Godan kata as an example.

The first three moves of Pinan Godan are shown below in photos one to three. Those motions are then repeated on the other side before a sotouke (photo four) is delivered to the front. These motions are commonly thought of as a block and punch to the left, a block and punch to the right, and then a block to the front (the hands held on the hips are given no function). One of the mistakes with interpretation is the common misunderstanding that the angles represent the angle of attack. We all know that getting an angle on the opponent is an important part of combat. When performing a solo kata, we don’t have a second person to establish the angle for the technique, so we have to use the centreline or our previous position. The angles in kata tell us the angle we should be in relation to our opponent when applying a technique.

Aside from the fact it is common sense, there are also some literal references to the fact that the angles in the Pinan kata show us the angle at which we should apply the technique (e.g. Kenwa Mabuni, founder of Shito-Ryu and a student of Itosu, makes this point in his book Karate-Do Nyumon). The opponent has grabbed your clothing. Shift at a 90-degree angle to take you away from any potential punch. As you move, you should smash your forearm on the opponent’s arm to disrupt their posture (photo five). This is the application of the ‘priming motion’ for the block. Smashing your arm into the opponent’s forearm will also set them up for a forearm strike to the base of their skull (photo six). You should then seize your opponent’s arm, in order to keep them and their posture disrupted, and deliver a punch to the side of their jaw (photo seven). Both the forearm strike to the base of the opponent’s skull and the punch to the jaw have the potential to knock out the opponent. However, if they are still conscious, the kata advises us to step in and crank the opponent’s neck (photo eight).

This is obviously a very dangerous technique and great care should be taken when practising it (which could be the reason the motion is performed slowly in the kata). If the opponent is still not fi nished, the kata advises us to secure a grip on their clothing, step forward and deliver an elbow strike to their face (photo nine). This is the function of the soto-uke. This is how kata should be interpreted. Notice how there are no impractical ‘blocks’, no hands held on the hip for no reason, and no strange hand positions that appear to serve no practical purpose. This application is close-range, practical and easy to apply. Interpreting kata in this way is very easy once people understand a number of basic concepts.

However, while understanding kata in this way is vitally important, it is still not the entirety of what kata has to offer. Once you have gained an understanding of the practical application of the techniques of the kata, you should begin to include variations of those techniques in your training. It should be remembered that a kata is meant to record an entire, stand-alone combative system. However, it would not be practical to record every single aspect of that system as the kata would become ridiculously long. It would be far better to record techniques that succinctly express the key principles of the system.

An analogy I like to use to explain how a form records a complete system is that of an acorn and an oak tree. An oak tree is vast, both in terms of its size and years lived, but everything about that tree and everything required to reproduce it, is found in a single acorn. A fighting system produces a kata in the same way that an oak tree produces acorns: both the acorn and the kata are not as vast as the thing that created them, but they record them perfectly. For an acorn to become an oak tree it must be correctly planted and nurtured.

Likewise, for a kata to become a fighting system it must be correctly studied and practised. It’s here that we find one of modern karate’s biggest failings, in that the kata are rarely studied sufficiently. To return to my analogy, we have the seeds but we don’t plant them! Hironori Otsuka, the founder of Wado-Ryu karate, wrote in his book Wado-Ryu Karate (page 19–20), “It is obvious that these kata must be trained and practised suffi ciently, but one must not be ‘stuck’ in them. One must withdraw from the kata to produce forms with no limits, or else it becomes useless. It is important to alter the form of the trained kata without hesitation, to produce countless other forms of training.

Essentially, it is a habit — created over long periods of training. Because it is a habit, it comes to life with no hesitation — by the subconscious mind.” I believe that Otsuka is telling us to practise varying the applications of the kata or else we’ll run the risk of being stuck in the form and becoming limited martial artists. We need to follow Otsuka’s advice and practise so that the principles within kata can be utilised, without hesitation, in any situation in which we should find ourselves.

Katas express good examples of the core principles of the combative system that is being recorded, they do not record every single technique, combination and variation in the entire system. How could they? So, to get the most out of kata we need to practise varying the techniques of the kata while staying true to the principles that the techniques represent. This is the third stage of kata practice. The fourth and most neglected stage is to practise applying the techniques, variations and principles of the kata in live training.

The only way to ensure that you will be able to utilise techniques in a live situation is to practise your techniques in live situations. You need to engage in unrehearsed, all-ranges free sparring if you are to make your kata training worthwhile. No amount of solo practice or drilling the techniques with a compliant partner will give you the skills needed to apply what you have learnt in a live situation.

In recent years we have seen more and more karateka begin to include bunkai practice in their training but, while this is to be applauded, it is of little use unless we take things one step further and engage in kata-based-sparring (visit www. iainabernethy.com for further details on the kata-based sparring concept). Live sparring and the solo performance of a kata may look radically different, but they are essentially exactly the same. As an analogy, think of a kata as being like a block of ice. The shape of the block of ice is constant, but if heat is added, the ice will turn into water and its shape will adapt to fit its circumstances. Likewise, a kata also is constant, but in the heat of combat it will also adapt to its circumstances.

The block of ice and the free-flowing water may look very different, but they are essentially identical (the same molecules of hydrogen and oxygen). In the same way, a form will often look different to the techniques being applied in an ever-changing, live fi ght, but they are also essentially identical (the same fi ghting principles). Although the four stages of kata practice may look different, all of them are identical at their core. All four stages are ‘kata’, not just the solo performance. These four stages are by no means unique to karate. In boxing, for example, a student would fi rst be taught the mechanics of the basic punches (stage one). They would then practise applying those punches against bags, focusmitts and a padded-up, compliant partner (stage two). Once competence has been achieved, the student would practise combinations, blending the punches, etc. (stage three).

And finally they would get in the ring and try it for real (stage four). While a student would initially start at stage one and progress to stage four, it should be remembered that the preceding stages should not be abandoned and they must also be practised. Stage-four practise is undoubtedly the most realistic; however, you should not abandon the other three stages when you are competent enough to engage in kata-based sparring. The practice of the solo form will allow you to refine technique, visualisation and mental attitude without the pressure induced by an opponent. It’s also a good way to train when your partners are unavailable.

The practice of the bunkai (stage two) and variations (stage three) will also help you to improve technique and ability to apply that technique. You will also become a more versatile fi ghter as your understanding of the kata’s core principles improves through stage-three training. Conversely, as your ability to apply the techniques of the kata in live practice increases, so will the quality of your solo form as the kata will become more meaningful and mentally intense. Karate’s katas truly are works of genius that have a great deal to offer the pragmatically minded karateka, but to unlock the whole of what katas have to offer, you need to practise them in their entirety. While the solo aspect of the form is very important, it only represents the fi rst stage. It is only when you move beyond the solo form onto the subsequent stages that it becomes apparent how pragmatic and holistic karate can be. □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, FEBRUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 02