THE RIGHT END OF THE STICK - Bobby Taboada

From tough street kid to disciplined eskrimador, grandmaster of Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) Bobby Taboada has come a long way since a rude and violent awakening at the wrong end of his master’s stick.

Now a world-renowned instructor of the Filipino stick and knife-fighting system Balintawak Eskrima, Grandmaster Taboada resides in the US but regularly takes his skills around the world. He recently visited Australia as a guest of his Melbourne-based student, instructor Garth Dicker, and gave this exclusive interview for Blitz following his seminar tour.

An interview with Grandmaster Bobby Taboada by Rick Mitchell.

Where are you now teaching and where else in the world do you have affiliate schools?

I’m based in America in Charlotte, North Carolina. Mostly, I teach private lessons at my home studio and sometimes I offer special group classes for instructors at my very good friend Irwin Carmichael’s Martial Arts Training Institute. Also, periodically, I’m invited by students who have schools in the United States and other countries, such as England, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the Philippines, to give them special training and conduct seminars. I have dozens of students who are qualified instructors throughout the world.

A lot of early FMA training was sanitized for the American market and stick fighting, rather than knife fighting, became the focus. (This has been said of Modern Arnis, which led the way in bringing FMA to the USA.) Did you also need to modify your Balintawak, or its training methods and syllabus, for the US?

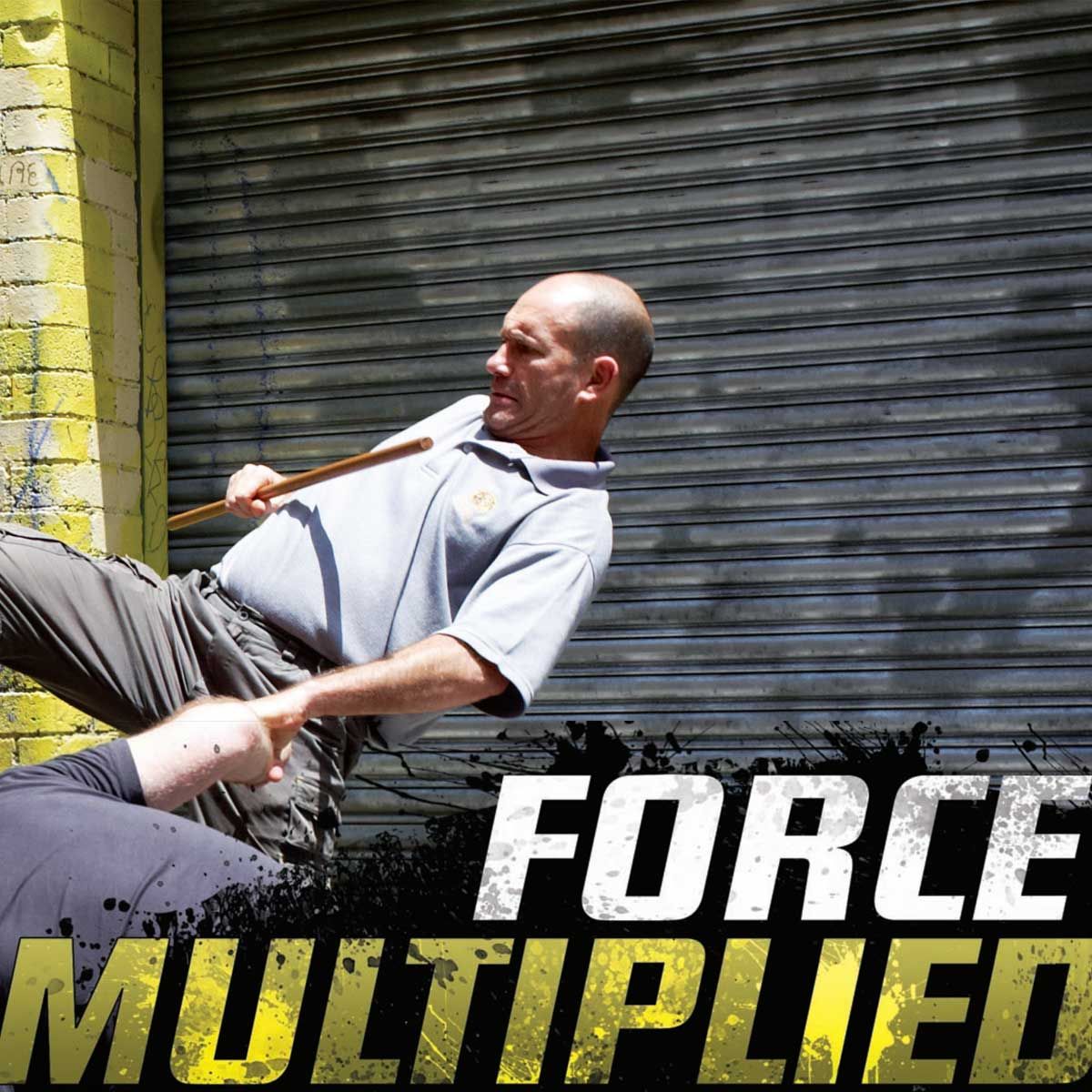

Yes. After leaving the Philippines in the late ’70s, I modified Balintawak from the original way so that students don’t get hurt. In the US and other Western countries, you have to be careful of potential lawsuits. Instead of the knife, I mostly emphasise that the students train with the stick first for safety. A knife is a lethal, offensive weapon and I want the students to know how to defend themselves first. Anyone can attack you with a stick or a blade. I don’t have to teach you how to do that.

It’s much more difficult to defend yourself. After students are trained and have developed the force, speed, reflexes and control necessary to defend themselves, then I allow them to attack. As you know, in a real fight there are no rules. It is a matter of life and death and if someone comes at me trying to kill me, I am not going to spend time blocking their strike — I will hit directly to their head instead. I’m not taking any chances. If I have a gun on me, I definitely will use that rather than a stick or knife.

Why did you leave home at age 12 to live with your master, Teofilo Velez, and what sort of advantage did that give you over other students? What was daily training like?

At age 12, I did not live with Teofilo Velez. At that age, I was mostly hanging out on the streets all the time. It was tough and I trained in karate and boxing for survival. It wasn’t until I was 19 that I started living and training at Mr Velez’s house. When I first met Mr Velez, he thought I had a bad attitude because I was always showing off my boxing and karate. One time, I told him I would show him my karate and boxing in exchange for him showing me Balintawak. He thought that was very disrespectful. So he poked and jabbed at me with his stick to get me agitated. Then I attacked back at him, but harder. Very quickly the contact escalated and he ended up throwing me in the pigsty that was next to our training area.

I had a slimy, bloody nose and I was humiliated! After that, for an entire year, Mr Velez had me only drill the 12 basic strikes and defences — I was sick of it! As I continued training at his place, I gained the advantage that anywhere someone tried to hit me, I could block the strike. This gave me extra incentive and insight into the importance of being well grounded in my basics so that I would become good. One time, Mr Velez’s demo partner couldn’t make it to a demonstration and Mr Velez was looking for another partner. I don’t know why, but I asked him, “Why don’t you choose me?” He thought about it for a moment and said, “Okay, prepare yourself for tomorrow. There will be no rehearsal.”

The next day at the start of the demonstration, Mr Velez announced to the crowd, “Good afternoon, my name is Teofilo Velez and,” pointing at me, he said, “this is my dummy!” I didn’t mind being called his dummy. I was just happy to be a partner with my master. But I was also extremely nervous and felt drained of energy. Right away, Mr Velez swung his stick at the left side of my body. He noticed that my blocking was very weak and loose and I lacked focus. Then he struck at my right side and my block was not there. He followed up with a strike at my head, which woke me up. After that, I was blocking all of his strikes and he could not hit me anymore. This worried him, so he grabbed my hand to control me. I didn’t know what to do next, so I grabbed his hand too and we ended up pulling back and forth at each other. Immediately, he transferred his stick from his right hand to his left hand and struck me all over my body until I was beat to a pulp and could not take it anymore.

This is when I found out that he was really left-handed! I lay down on the ground and lots of blood started dripping from my head. Everyone came over to Mr Velez to congratulate him for the excellent demo and a few people came up to me with pity and just looked at my cuts and said, “Poor guy!” When we got home, all of the other students were already there at the house. They all congratulated Mr Velez and were looking at me like I was a disgrace. As I stood in the corner of the room with blood still on me, which I purposely didn’t wipe off, Mr Velez looked over at me and said, “That’s the guy I like!” Then he walked up to me and said, “Let me look at that cut… why didn’t you block my strike?” I said, “Well, you were holding my hand, so I held your hand too. Then you transferred your stick to your left side started hitting me.”

Mr. Velez replied, “Yes, and when I held your hand why didn’t you do Group One – the lifting and clearing technique?” I said, “Nobody taught me that.” Mr Velez asked his eldest son, “Chito, why didn’t you teach him Group One?” Chito said, “You told me not to teach it to him because he’s a showoff!” After that, Mr Velez started teaching me more of the curriculum — Group Two, Group Three, and so on. Eventually, he let me teach the classes. As he did that, he stood at the side and analysed what I did wrong. He would then demonstrate on me how to do it correctly. In the process, I would have to take hard, painful blows, which I just accepted as part of my daily training. It took a long time for me to earn his respect, but once I did, he opened up to me and showed me a lot. He took me on as a protégé and that’s when I really started learning.

I’m told you once came to have to defend yourself with a stick against lots of men with swords/blades in the Philippines. How did this incident occur, and what did it teach you in regards to fighting multiple attackers?

I was working at the pier as a gangway man for a shipping company in Cebu. It was 11 o’clock in the morning and I was next to the kitchen where chief cook was preparing lunch. Another worker went into the kitchen and was taking food without asking or paying for it. I told him he couldn’t do that and he got very upset and walked out the door with an angry look on his face. Later in the afternoon, someone came running up to me and said, “Bobby, watch out that guy’s coming back and he has a lot of his buddies with him!” I looked past where the passengers were coming in to board the ship and could see out in the distance about five of them with shiny swords in their hands.

I said to myself, “Oh shit, why did I have open my big mouth?!” I ran to the kitchen and asked the cook if he had a gun. He said he didn’t have one. So I asked him for a knife, but he wouldn’t give it to me. I tried to run, but I could not get away because the people on the ship saw me and were clapping their hands and cheering me on. They wanted to see a fight! Just then I remembered that this old man kept a bahi (hardwood) stick at the top of a stack of palettes. I ran to the palettes, reached up at the top and grabbed the stick. I yelled out, “Everyone keep away from me. Anyone who comes near me will get hit!” As I watched those thugs come nearer and nearer, my heart started pounding and I felt like I was walking on air.

Once they got close to me, I felt like I was in a Bruce Lee movie. Everything was like it was in slow motion. At first, I baited them by acting like I was running away. Then instantly, I spun around and swung my stick straight at their heads as if I were busting open coconuts. Everyone I hit got knocked out. This experience taught me valuable lessons when it comes to reality and fi ghting multiple opponents. I realised that when training with my masters, I had to exercise self-control and not hit back, and it made me crave for the opportunity to make contact.

My masters always emphasised, “Defence, defence, defence,” and to practise at full speed to develop my reflexes. And that’s what I did. So when I finally had the chance to hit back, it was like slow motion because I could hit with full speed and power and not hold back. I found that my speed was even faster than in practice because I could let loose and not have to block and then stop my counter-strikes before hitting the target anymore. Also, all of my strikes went directly to the head. Before my opponents could strike me, they were hit already. When fighting multiple opponents, especially ones with blades, there is no time to first block their strikes and then counter. It’s best to go on the offensive and hit the head straight away.

Is multiple-attacker defense part of your teaching today?

Yes. Part of our curriculum is the semi-hitting drill. In semi-hitting, as our partner’s strike is being delivered, we strike one or more times to their body before blocking. Once you are used to hitting, let’s say, six times before blocking, it is very easy to hit one time before blocking the opponent’s attack. This drill was very helpful in preparing to fight multiple opponents because it taught me to strike very quickly to take care of one opponent before they could hit me, and then immediately move on to another opponent.

Also, I teach my students how to stand their ground while fighting multiple attackers. The way I teach this is through a special footwork training drill. In this drill, students learn to use quick and economical shifts of the body while at the same time cocking their stick back to power position so that they can instantly face attackers surrounding them and then strike them with power. There is no need to jump around all over the place like a monkey.

Has your manner of teaching and training changed as you’ve grown older?

Yes, a big change in my manner of teaching and training happened as I got older. Over the years, I was able to analyse all of my masters’ techniques and I gradually added my own techniques to the art. The way I came up with my own techniques was by thinking about how to counter the moves my masters taught me. And I encourage my students to do the same; to think about how to counter the techniques I show them. In my program, I’ve made it a requirement for students to create and demonstrate 24 of their own techniques for promotion to qualified instructor. This forces them to research other styles and to draw from any previous martial arts background and experience they have. This is how the art will continue to grow. Another thing that changed is the hard and brutal teaching method I learned from my masters.

After leaving the Philippines and moving to New Zealand and then the United States, I figured out a way to safely teach people the basic movements of Balintawak without hurting them. If I strictly taught the traditional way, students would get hurt and wouldn’t want to continue learning. They might even try to sue me! Sometimes when students get to be more advanced they will ask me to train them the way my masters trained me. If the students have completed the system of basics in my curriculum and I see they have the skill and control necessary to defend themselves, I will ask, “Are you ready to accept the pain?” If their answer is yes, then during agak (the ‘play’; a sparring drill where the instructor randomly ‘feeds’ the students controlled strikes to different parts of their body and the students immediately react with a pre-set defence and counter-strike), I will strike them with a certain amount of increased force to their body so that they will experience what it is like to get hit.

While training them, I urge them not to lose their focus and to concentrate on executing proper technique instead of the pain. I really have to be careful when selecting the students I teach this to because I don’t want to have the liability and possibly go to court. Another thing I’ve come to realise is that it’s important to keep people interested and teach things they want to learn. So, I’ve added to my teaching some fun drills, twirling exercises, and what I call ‘Hollywood’ or fancy techniques. Besides that, I make sure when teaching and interacting with people that I am friendly and respectful with everybody. If I’m not friendly and respectful, no one will want to associate or train with me. That’s why I am welcome to demonstrate and teach in the schools of people who practise different martial arts, such as karate, kung fu, taekwondo, etc. I respect them and their arts and they respect me and my art.

Check out part two in next issue for GM Taboada’s thoughts on practical knife defense, FMA in Australia, training in the Philippines and more.□

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine MARCH 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 03