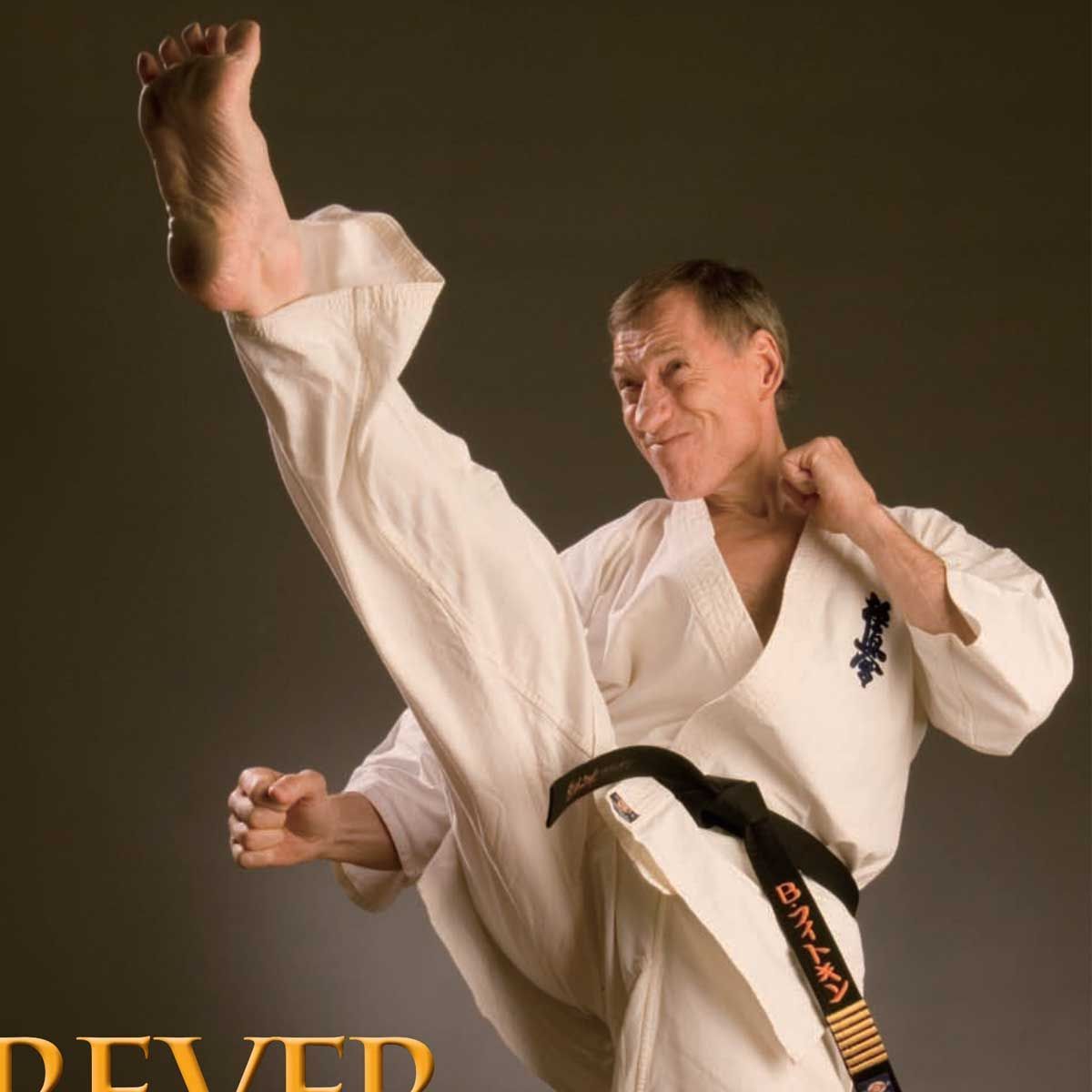

FORCE MULTIPLIED - Eyal Yanilov

You’ve put in years of hard slog in the dojo, and never had a problem putting even the toughest fellow Black-belts on the back foot in the sparring. But how do you feel when your mates have gone and a group of guys decides to follow you outside the nightclub and beat you beyond recognition, all for an accidental dancefloor bump? Are you prepared? Fearful but confident?

Most martial artists wouldn’t be. Yet that’s where Israeli military-based fighting system Krav Maga excels. Here, International Krav Maga Federation chief Eyal Yanilov, who recently visited Australia, and Aussie IKMF representative and Blitz columnist Graham Kuerschner, break down the Krav Maga approach to training for the ultimate self-defense nightmare.

Krav Maga methods for fighting multiple-attackers.

INTERVIEW BY BEN STONE

THE ULTIMATE TEST

We need to accept that being caught up in a multiple opponent attack is a very serious thing. In Krav Maga, we take the attitude that they intend to kill us, and we fight as if this were true. And in the end, even if we come out wounded but are still alive, then we are lucky. That said, most multiple opponent attacks — as with most single-attacker scenarios — do not start all of a sudden but are preceded by aggressive behavior on the part of the potential attackers. This behavior is a signal of potential violence and gives the would be victim a chance to be proactive. If they cannot escape the situation — which is the best option — they can at least be in a position to make the best of a bad situation.

Many such attacks occur against people who have been subconsciously selected based on the attackers’ assessment of that person’s vulnerability, or characteristics that make that person stand out. So, you should first consider what might make you appear vulnerable or stand out to others in order to try to decrease your chances of being selected. In the pre-fight stage (that is, before the real physical attack) we try to avoid, prevent or de-escalate the situation. And if actions such as escaping or distancing to get away from the danger zone fail, then we move on to the next set of tactics. This might include re-positioning ourselves to be facing all opponents and avoiding someone circling around to get to our rear; preemptive attacks; equipping ourselves with a handy object that will assist as either a weapon or a shield; recruiting assistance from other people; posturing using verbal threats and aggressive positioning; and so on.

Once the fight has begun, the key is not to be surrounded or flanked by your opponents. For this, Krav Maga offers specific maneuvers to position oneself in a way that causes all the attackers to be in a ‘funnel’ area in front of you. This is done while performing whatever attacks or counterattacks are required. There are also further tactics and techniques to ensure the aggressors will not circle around us or use weapons or objects against us. These include maneuvers, control techniques, manipulation of body position (ours and the aggressors’), retrieval of tools and weapons, and more.

TRAINING FOR NUMBERS

In training students to deal with multiple attackers both physically and mentally, Krav Maga employs a range of methods from the simple to the more challenging, depending on the capability and experience of the student. For beginners, simple ‘functional games’ enable trainees to learn basic positioning skills against multiple attackers.

In these drills, attacks are divided into ‘families’ or groups (strikes, kicks, grabs, edged weapons, etc). At first students train in dealing with certain families of attacks only and then as they progress, the limitations start to drop and attackers can use all the offensive methods they wish. Likewise, we may initially limit attackers in respect of how often they can attack — for example, they may have to pause for a second or two after each strike. At higher levels, this limitation is reduced and then removed. Initially, we start with one-on-one scenarios before adding a second attacker, then a third and later a fourth attacker. Aggressors attack individually or in a group, as they wish, with no limitation as to when they can attack, just when they join the group. Later on, all can start at the same time.

In early training, no weapons are used (by either side), but are introduced at a later stage. A weapon can be a great equalizer when facing a group attack, so where it is appropriate and legal, we recommend that people carry weapons for self-defenses, but usually we suggest common objects that can be used as weapons. We teach how to identify and retrieve such objects as well as how to use them, meaning, how to defend and/or attack with the tool (originally a common object that becomes an improvised tool/weapon for self-defense). We teach how to use such tools to threaten — that is, ‘posture’ to deter an attack — and also how to control others with such objects.

In the Krav Maga system we divide the common objects into different families — e.g. shield-like objects, others that may be used as impact weapons, small objects for distraction, rope or whip-like objects, etc. — and teach the principles of use for each family. Krav Maga employs a number of predefined technical and physical drills to train for multiple opponents. By ‘technical’ we mean predefined technique to be used, and by ‘physical’ we mean a goal has to be achieved, by physical means, against the odds. This requires mental determination.

On the mental side, we also have drills to improve our ability to divide our focus or to disperse our attention when faced with multiple threats. Through other drills we learn to elevate our level of aggression to match the situation and to make tactical decisions while under stress and dealing with a mass of confusing and conflicting information. We use specific visualization and mental drills, including the planning and executing of simulated scenarios. But talking theory only gets us so far. One has to be in the middle of the trouble to feel the experience, to solve the tactical problems and become more effective and efficient. If you don’t do scenario training, especially in varied locations and terrain, it’s like reading about love (or war) but never experiencing it.

This is where many martial arts schools — of those few who even bother to address multiple-attacker training — fail when it comes to training for multiple attackers: in the level of reality. In drills, the attackers do not attack as would likely be done on the street; for example, they time their attacks in partial co-operation with, or at the convenience of, the defender, or they only attack in a predefined way.

RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT

The International Krav Maga Federation has developed its approach to dealing with multiple attackers a good deal since the early days, when the types of problems and responses trained for were simpler. In the 1960s and ’70s we dealt with situations where one or two attackers may hold you while a second or third attacked from the front.

In the early ’80s we extended this to situations against two armed attackers, one with a stick and one with a knife. The training involved determining how to deal with this problem (evaluation, positioning and technical solutions).

In the mid- ’80s this was extended to drills with four versus one. From the early ’90s, with the increasing variety and sophistication of multiple opponent attacks, we started dealing with an array of problems in a variety of environments. Since the late ‘90s we have placed greater emphasis on tactics in the drills and scenarios as well as the psychological elements, which are critical in situations where the odds are against you. The research and experience that forms the basis for Krav Maga’s current multipleattacker training curriculum comes from both the military/ law-enforcement fields and civilian studies. Information on the types of problems that arise in multiple-opponent situations, as well as some of the natural (untrained) responses to such problems and other potential solutions to them, is garnered from all those areas (although it mainly comes from within Israel).

Using this information as input, we conduct many experiments under similar real-life conditions and make our assessments as to potential solutions. The results of this research are principles and general technical solutions that are taught to both civilians and law-enforcement personnel, taking into account the different aims of these groups. The differences in teaching these two groups are usually in the pre-fight and post-fight stages, as soldiers and police officers have professional duties to perform. The equipment and weapons carried by the professionals also changes their way of operating and some of the specific tactics they may use. Police officers and soldiers will generally operate with a tool (e.g. baton, pepper spray, etc.) or weapon in hand, and may have a fellow officer close by to assist. Their professional duties, such as arresting people, or killing or capturing terrorists, will of course dictate their actions as distinct from civilians.

KRAV MAGA IN AUSTRALIA

“Krav Maga, as we see it, is the distilled learning of the Israeli experience of fullspectrum violence — from street crime to violent political protests, to terrorist attacks, to war — on a continuous basis over the last 50 years. As a defensive tactics organisation based in Israel, this is what distinguishes what the IKMF has to offer from other systems based in other countries,” says Graham Kuerschner, Australian IKMF representative. “The growth of interest in Krav Maga Down Under has been strong in both the civilian and professional sectors to the extent it is causing us to have to change our operational structures.

The IKMF is the largest defensive tactics organisation in the world (Israeli or otherwise) and large organisations can readily have problems with quality because of the large numbers involved. We are challenged to maintain the same high standard in all our schools from Sydney to Santiago, to Singapore to Siberia (yes, we operate there) and everywhere in between. “Now part of maintaining quality is staying up to date with changes as we learn new things from our experiences in Israel and the particular challenge in Australia is that it is quite a distance from Israel. Nonetheless, Eyal and one of his other senior Israeli instructors come here at least twice a year to teach and a number of the senior instructors out of more than 45 Australian instructors come to Israel and Europe each year to train.

“From these efforts, we hope that something good can come from our bad experiences.” □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine MARCH 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 03