KARATE FROM THE HEART

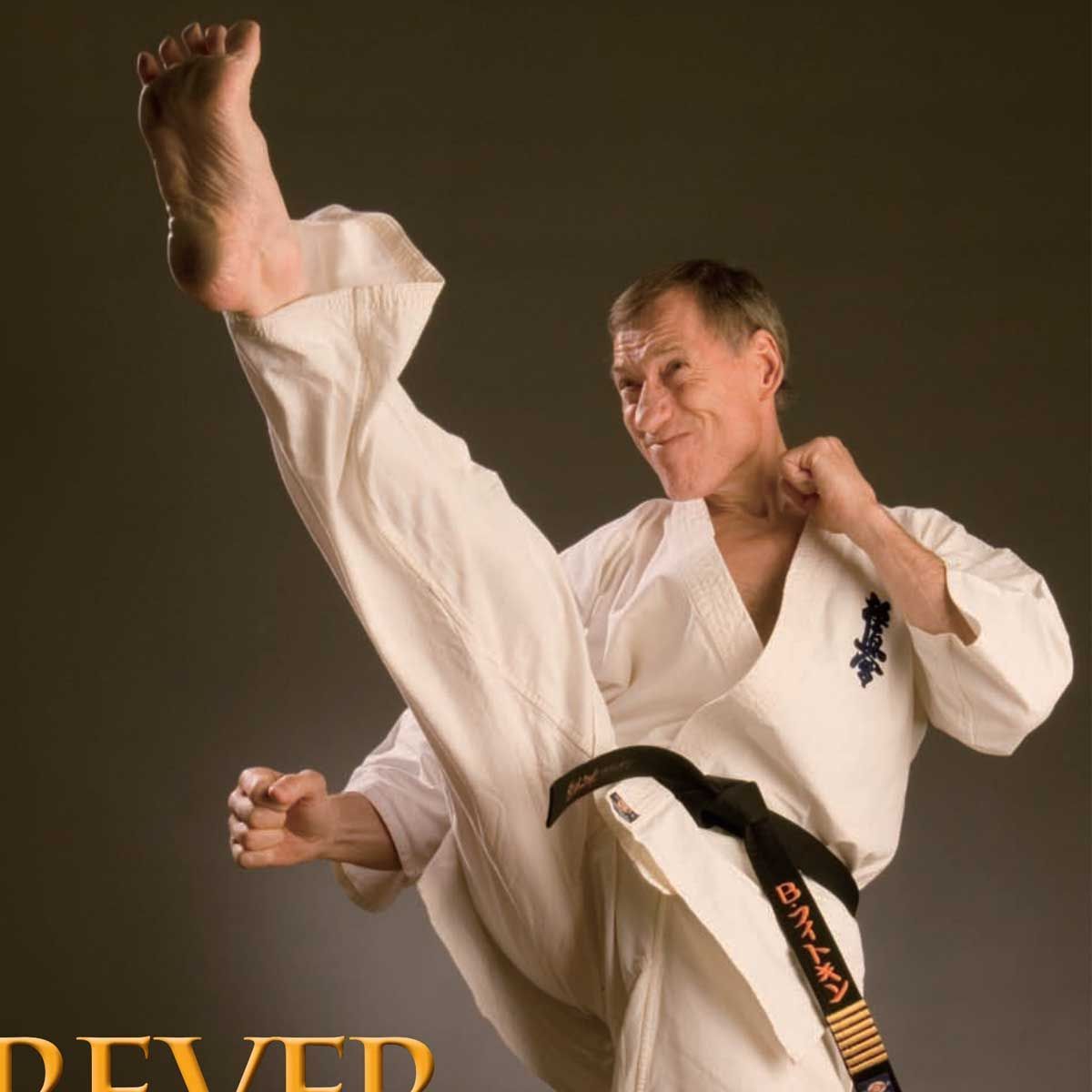

There would be few senior Shotokan karateka practitioners in the world who have not heard the name Stan Schmidt. Quite simply, he is a legend among those who follow that particular school of Japanese karate.

And while his depth of karate knowledge and achievements are undeniable, like so many legends, the person behind this one is much closer to normal than the myth might have us believe.

Mike Clarke spoke to Sensei Schmidt and discovered a remarkable man who is also a ‘regular guy’.

STORY BY MIKE CLARKE

At the time of our conversation, Sensei Schmidt (or Stan, as he preferred I called him), was 73 years old and still practicing the art he began studying as a young man in his native South Africa back in the late 1950s. Like many of that era, he was introduced to karate through judo, which, along with jujutsu, had been established in the Western world for some years.

Already training in judo, in which he achieved 1st Dan, it was an accident resulting in a broken ankle that proved decisive in his switch to karate. During his recovery Schmidt was given a book on karate, a martial art few in the West had heard of back then, and in it he read a line that changed the course of his entire life: “The karate man never stops training.” Capturing his imagination like nothing else he had known, this single line caused him to jump headlong into karate training. In the absence of an instructor, he gleaned what he could from the few books he was able to find. In this way he began to absorb an art he was destined to practice for the rest of his life.

Then in 1963, he went to Japan to seek proper instruction in Shotokan karate. His introduction to formal training came as something of a shock, as a confused conversation found him placed in the general training class where he was the only ungraded student in the dojo. Still, he was young, strong and full of spirit, and this proved enough to get him through the schooling he found himself involved in.

With intensive daily training and a lot of help from his seniors, he left for home wearing a Brown-belt, and was now in a position to introduce authentic Japanese karate to his homeland. In 1965, he hosted the late Keinosuke Enoeda, who lived at his home for six months, taking the standard of Shotokan karate in South Africa to a new level. The story of karate in that part of the world, and Shotokan in particular, would be different today had the young judoka not broken his ankle and discovered the art of karate in the pages of a book.

Today Sensei Schmidt is the senior non-Japanese sensei within the Japan Karate Association, a member of the JKA Shihan-kai, and regularly sits on the panel of examiners for higher Dan gradings. Along with his family he moved to Australia, but still visits South Africa and Japan from time to time. At home in Melbourne he teaches a small number of students in his private dojo and is as enthusiastic about karate now as he ever was.

Our conversation ran, on and off, over a number of weeks, and what follows here is only an abridged version of it. Few Western karateka have practiced their art continually for almost 60 years, and even fewer have made the sort of contribution to furthering the understanding of what karate is than Stan Schmidt. Hopefully you will fi nd his views as fascinating as I did.

Stan, it feels a little strange for me to be addressing such a senior karateka by their first name, but as you prefer I do, I’m happy to comply. It’s being respectful of each other that matters, not the title; Stan is fine. Well Stan, to begin, what particular challenges do you face as you continue to train karate into your 70s?

I think I’m fortunate in that I have trained in karate since I was young and still do. In that time I have had various injuries and both hips replaced after a motorcar accident, but I believe my training helped me deal with that.

My main purpose at the moment, for my personal training, revolves around what I call ‘contra-indicators’ in my training and in my technique. I realize these won’t be the same for everyone, because everybody is different. But I am finding that (A), because of my age, and (B) because of restrictions and limitations due to the hip replacements done during my 50s — as well as some of the type of training I did when I was younger — all of these things have caused me to refi ne the techniques so they don’t do any harm to my hip joints, but actually rehabilitate them as I continue to practice.

For example, in the opening movements of the kata Heian Shodan where you move from the yoi (ready) position to the gedan-barai (downward block) position to the left, I had previously done what most people do and pivoted on the ball of the right foot as I shot the left foot forwards. So this, in my opinion, is contra-indicated over a long period of time, especially if you train on certain surfaces that can cause the feet to over grip, like on a rubber mat or grass etc. Trying to move as I’ve just described on most surfaces can work against different joints, especially the ankles, the hips, and the knee joints. Whereas if you lightly turn your toes of the right foot, and stay on your heel to pivot 45 degrees to the left to do the block, it is a very freeing movement.

If this kind of movement is educated — in other words, if it is repeated a lot — it becomes free flowing, and thus quicker. This is just one example around the idea of executing flowing, rather than forced movements. Right now there are two really big no-no’s for me. One of them is yokogeri-keage (side snap-kick), and the other is making a long stance while doing gyakuzuki (reverse punch). These two things are very dangerous for certain types of Western people who may for example have a long femur — you know, long legs but with short bodies.

My height has altered since my hip replacements, but basically I’m 6’2”, so quite tall. Some tall people who haven’t had hip problems develop knee problems; so I think maybe there is a weak point here (in the legs). Because the Japanese drilled us over the years to do a technique a certain way, we tried to copy them and do it exactly as they did. But most of us have different bodies and so rather than train in ways that grind down our cartilage or is damaging ligaments and things like that, we should be training in ways that don’t damage the body.

The problem is, the damage isn’t always obvious, it may not happen straight away, but may take a few years to manifest. My main focus of thinking today, is to help others to learn how to monitor themselves as they move backwards and forwards, sideways, and up and down, so they are not damaging themselves with overly elongated or awkward movements.

An example: If, say, you are already in a stable zenkutsu dachi (forward stance), but then you elongate that stance (like some people doing Shotokan in England and we in South Africa used to do), this is what I call a ‘contra-indicated’ move. I was watching an old tape of ours recently and thought how ridiculous everyone looked. Biomechanics to one side for a moment, it was clear there was no sense of free flowing movement; the body was just being worn down by forcing a punch or kick.

Do you think Western people have been misguidedly trying to mimic the Japanese, then, instead of trying to learn the principles involved and employ them in ways conducive to their own bodies?

Yes and no. Don’t get me wrong though, there are Japanese who shouldn’t be doing those long movements and postures either. Funakoshi Sensei’s karate didn’t look like this. A lot of people have labelled Shotokan karate a long-distance type of fighting whereas Goju-ryu is more close-quarter fighting, but most fights end up at close quarters and it might be better if people think of karate as both. Breathing and free flowing movement are important, no matter what range you fight at.

Many years ago, I made a point of studying lions and how they fight, live and hunt, because lions are extremely relaxed creatures. I remember I had Masahiko Tanaka staying with me at the time. One day, as we were walking down the street, he looked at me and said, “Stan, why you so tense?” I was surprised because I didn’t think I was. Although, when I thought about it I realized I was completely out of alignment; my shoulders were hunched over and my backside was sticking out — terrible! Another time I was playing a round of golf with an old friend of mine, Wayne Westner. So there we were afterwards on the driving range and I’m hitting the ball about 150 metres or so. He came along and drove the ball around 300 metres or more.

Wow! So I asked him how he did this. “Stan, just look at your feet.” Where I had been standing there were two big pits in the ground where my feet had been, and the grass was all torn up from twisting. Comparing that to where Wayne had stood, where the grass was still smooth and green and looked as if no one had ever stood there. He told me then, “You have to be soft-footed and relaxed to hit the ball far, not heavy and over-strong.” Yeah, I want be more like a lion.

These experiences were pointing me towards being softer, but it wasn’t until after my accident, when I was in my 50s, that I had to become soft. I had to find a way of still being strong but from softness, and this is what I believe in now for all karateka. I’m learning something new every day and I still try to train at least six days a week. Sometimes it’s only for 10 or 15 minutes or so, and sometimes it’s for an hour-and-a -half. I try to do something on most days. But I never train with so much tension that I walk out of the dojo with unhealthy aches and pains.

I think many people mistakenly pursue perfection of technique over developing a natural feeling for it. So they spend their time working on every little bit of technical detail, and miss out on the natural rhythm of the technique and how best to apply it.

What are your feelings about this?

Yes, I call it ‘paralysis of analysis’. Look, I’m not a good golfer, but I think golf and other sports can show us how we should move. Nakayama Sensei would sometimes talk to us about this. He would explain how baseball players and golfers stayed relaxed when they hit the ball, they never tensed up but instead worked towards a tremendous release of energy as they hit through the ball.

When they got it right there was the same exchange of energy we might call kime (focus) in karate. He told us that this is how we should try to be and not get all bound up (with energy) before making a blow, or whatever technique we were doing. I think that is the secret to developing power from softness. I do a lot of reflex training drills from a relaxed/ready posture.

Do you think there is too much emphasis placed on making kime then?

Well, I think the kime in a punch should be something like a 50th of a second, something like that, so yes, some people may be putting too much emphasis on kime. But then when we practise Hangetsu kata in Shotokan, and you have Sanchin kata in Goju-ryu, the tension is different and is held for longer to develop core body strength. But with a fast, sharp, kizami-zuki (leading-hand punch) or ura-ken (back-fist strike), or even a mawashi geri (round-kick), the kime should be there but for only a fraction of a second before the release comes and you are ready for the next technique.

This is the kind of thing my students and I are working on. It also comes up during smooth aerobic training when you might be doing kata over and over. Suddenly in the middle of a kata you get to the point of kiai (harmony of spirit and technique) and kime happens without conscious effort.

So even at an advanced age such as yours (73), you feel your karate is still physically strong?

To a degree. I look at a person’s biological age I don’t look at age chronologically. How old are you? I’m 54. That is still quite young, but more importantly you sound like you are doing all the right things, not doing stupid things to harm your health. So your biological age is probably much younger than your chronological age because you keep yourself fit, train regularly and stay healthy. I can say that in only about 20 per cent of my karate, things are better now than when I was younger. When I go to a gasshuku to teach I can no longer do all the jumping and running around that young karateka do, but there are a few things I can do against younger and stronger people when we stand facing each other within punching range.

For example, we sometimes do a drill where you stand within range of your partners punch, they throw a punch and you have to use reflex action to block it. I can still do this and make the block. Also I am still quite fast with my punching. But, if I had to start moving around all over the place and fighting at longer ranges then I’m no longer efficient. So I work on the things I can still do well and improve as best I can. For example, when a young man is taking the test for Shodan (1st Dan) Black-belt. They have been training for something like four or five years and have come through the Brown-belt ranks where they learn to hit the makiwara. During that time they might be throwing 50 or 100 punches on each side, but they tend to do all the punches at the exact same rate, exerting that same amount of energy (kime).

They do that and then they do whatever kata they are requested to do and that’s it. They go through the ritual and that’s that. A lot of people don’t change from training this way after Shodan. What I’m doing is looking at how I move from point A to point B. These two points might be anything; the fist moving from the hip to its target, or the leg moving from one position to the next. What I’m doing is working on the efficiency of the movement. So now when I hit a target, I don’t hit the makiwara anymore, I hit a bag. Not one that is too heavy, but it’s not too light either. I hit that as well as I can, but not too many times. It’s a bit like a weightlifter who wants to increase his power — what does he do?

He builds up to it with a lot of good form and lighter repetition first and then gradually increases the weight. As his lifts become heavier, he is breaking down the muscle tissue correctly, which then builds itself back up a little stronger than before. So he might do six reps and then have a rest, and then four reps and slowly work at doing heavier lifts, but less reps in order to increase his power. I have taken this same approach to punching and bag work over the last 10 years and I can say now that the strength of my punching compared to when I was 60, has improved a great deal, in particular with a choku-zuki (straight punch) standing in a relaxed forward stance and shooting the punch into the bag. I begin by standing in front of the bag and punching straight into it. Next I take up a relaxed forward stance, turn my hips and punch the bag.

The next stage I take a slightly longer stance and draw the back foot forward while simultaneously punching the bag. My most powerful punch occurs during the stepping phase when I am a quarter or half forward, or sometimes even three-quarters forward; the distance I start away from the bag governs this. I do no more than 10 reps of each technique just to warm into it.

My final seven punches are with full power but with my body moving as fast as possible. My fist, as it contacts the bag is vertical and not fully turned. I believe the final turn or twist in the fist in a punch is the follow-through, like in golf: after you have hit the ball, you continue on with the swing. I mean, when you hit someone, the guy’s no longer there when you initiate the twist. There might be an occasion when someone runs in at you and you extend your punch like a pole and they run onto it and knock themselves out.

In these last 10 years this has been maybe the one really good improvement for me personally. Now, I’m not saying I have the same power in my punch as someone like say, Keith Geyer, who hits on the scale of something like 8.8 out of 10. He can knock guys out even through a pad. But for me, I used to be around 6.5 at the age of 60 whereas now I’m more like 7.5, and this is with less training than before but with using the proper biomechanical principles. The principles are to break the movements down and how to use things like leverage to hit harder — like weightlifters use leverage to manipulate the weight. They should not be confused with bodybuilders, who pursue a different discipline.

What weightlifters do is closer to what we do in karate than bodybuilders. There are many things I would not attempt anymore, like kicks or jodan mawashi-geri (head-height round-kick), even though I still teach these techniques to younger people. In the world of Shotokan karate, Sensei Stan Schmidt is a household name. Having trained in the original Japanese brand of karate since 1962 (and earning a judo Black-belt before that), the 73-year-old 8th Dan is today the Japan Karate Association’s most senior non-Japanese karateka. Best known for making his home country of South Africa a recognized powerhouse in world karate, the pioneering instructor has almost 60 years of martial arts training under his belt.

Although today he lives in Melbourne and teaches just a select group of students at his home, he remains adherent to the quote from a 1950s karate book that first drew him to the art: “The karate man never stops training.” Here, Mike Clarke continues his conversation with Sensei Schmidt from last issue.

Stan, in your training these days, you emphasize developing a powerful punch — are you adhering to the principle of ikken-hisatsu or ‘one hit, one kill’?

Yes, this is an ongoing challenge. In my younger days, if a guy challenged me, I was very macho and all I wanted to do was knock him out or make him tap out, that was my main aim. But today my attitude is exactly the opposite; I want my blocks to be like lightning. So if a guy comes towards me, I want a block that will just shoot out and powerfully hone in on the attacker’s arm. I don’t believe in practising blocks against someone who is only throwing straight punches like oi-zuki (front-hand punch) or gyaku-zuki (reverse punch) — that’s okay for the lower Kyu-grade students, but not every attacker would come at you like that in real life.

So for Black-belts, I prefer to have them swing a punch at me free-fighter style. I try to catch a nerve on their arm, and this hurts.

This is my aim, more to hurt someone to convince them to stop. I don’t want to kill anyone; I would hate to have that on my conscience. In a way I’m still looking for that ‘killing’ blow, but not in the literal sense, only in the sense that it brings the fight to an end by killing his will to continue. If it came to a real fight, I would try to calm the situation down first, use my inner or spiritual strength if you like. I believe karate training brings us to this way of thinking.

So what’s going on inside the mind is vital to the success of the technique, is that what you’re saying?

Yes! Without this, the techniques are not as effective as they might be. There is a saying in karate, ‘spirit first, then technique’, so this is a clue. Let’s take a look at being in a situation where you might be feeling like you’re a coward; I’ve had this happen to me and maybe you have too.

I made a wrong judgment and I should have done something about it, but I didn’t. I can see now that it was my spirit that was wrong. I’m not talking religion here, I’m talking about how I was feeling at the time. Okay, so I’m in Japan, I’m taking the test for 7th Dan, and I’m in the middle of the grading. I was already having problems with my hips at that time because of an accident, and people knew this. We completed the kumite (sparring) section where there were three of us going for 7th Dan, a couple more going for 6th Dan and some going for 5th Dan. After I finished the kumite test, the others stood and clapped.

Then it came to kata and we each had to choose a kata to demonstrate and, out of fear, I chose Tekki Sandan as I didn’t have to move around too much and because I was trying to avoid causing more pain from my hips. I did it very quickly to get it over with but the grading panel wasn’t happy and asked me to choose a different kata next time. I returned home to South Africa and I asked my surgeon if doing kata would damage my hips and affect the upcoming surgery. He said, “No, it’s not a problem; go for it!” He would be replacing the hips anyway, so it made no difference from his point of view. When I went back to Japan six months later and re-took the kata element of the test, even though my hips were still painful, I did it with a completely different spirit.

The kata I chose was Chinte. Everything worked out fi ne and I was promoted; but you see, I made a bad choice out of fear when I walked onto the dojo floor the first time. You’re not supposed to be fearful of anything — only God! But isn’t this how we learn, through experience? Experience gives us the test first and the lesson afterwards, don’t you think? (Laughing) Yes, that’s exactly right, my friend. At first I felt like killing the examiners, but time is a great healer. I had six months to reflect on my actions and I look back now and realize that the experience was good for me. I proved to myself that I could overcome a pretty serious obstacle like the pain from my hips, and afterwards I felt quite proud of myself for going straight back and trying again.

Given the commercialization of the martial arts these days, do you think today’s students are learning such lessons?

I don’t have a problem with commercialism to a point, but when it gets out of hand it can be detrimental to the status of karatedo. There is the problem of some groups guaranteeing Black-belts and things like that, or allowing unqualified people to open up clubs and start teaching. I have seen people around the world and even here in Australia doing this. This kind of thing defeats the noble purpose of karate; you can’t promise someone a Black-belt in so many months, it’s not possible. On the other hand, if you are receiving good quality instruction and the classes are designed for different levels of student and things like that; the instructor is there all the time and they are charging a fee and paying their rent, then for me that is fine. Otherwise you’ll never propagate the art and it will die away in someone’s backyard.

Some commercial instructors seem unable to strike a balance between the money they’re making and propagating the art; and many of them are, at best, compromised by their dependency on students for income or, at worst, unqualified to teach. What do you think? Some so-called instructors are messing people up by having them do complicated movements that are, or will, cause injuries later on. There are also people who don’t really want their students to improve, so they keep them down by telling them they’re hopeless or by beating them up, emotionally or physically. The last thing they want is to advance their students. For me it’s important to push people above your own level, to have them stand on your shoulders. I don’t know many people who make their living solely from teaching karate. I have never relied solely on karate for a living. I’m very lucky teaching karate in that I have been able to draw people to me, but my working life began in a bank where I stayed for 11 years.

This allowed me to buy a house and begin to set myself up financially. Had I tried to live just off karate all my life, I would not be in the position I am in today. I moved into property development and that is where I made some money. I would invest in a property and sell it five or six years later for a profit, and in this way I was able to move on to another property. I quite agree; I think there are only a few people who make a living exclusively from karate and remain fair. I have to admit that, for a time, a lot of my income was from karate, but this had more to do with a particular set of circumstances coming together than by design on my part. I think I was one of the first karate Black-belts in South Africa and when the ‘golden era’ of the Bruce Lee boom hit, I was in a position where people were coming out of the woodwork to train in karate.

So I opened a full-time dojo and it did very well. But when others came through the ranks and wanted to open their own dojo I did not try to stop them, nor did I have any financial connection to them. From a commercial point of view I could have done a lot better and perhaps become a karate millionaire, but that was not my aim; I never had the desire to franchise my karate. Had you gone that way, do you think you would have been able to remain close to the spirit of karate, or would it have just become your job, like any other job? I had a chance to take my karate in other directions — the movies, for example. I enjoyed participating in the first two movies, Kill or Be killed and Kill and Kill Again — I hate those titles! When I was involved in American Ninja 2, I worked on the fight choreography and also supplied extras for the fight scenes together with Norman Robinson. It was a big production, but I wasn’t happy.

The way people were used and dealt with by some of those in charge was a real education in human misbehavior. So about threequarters of the way through the shooting of the movie, I asked Norman to take over. Some of the production people and actors were very nice, but I still decided to pull out. I’d had enough and I went back to my dojo. Maybe I could have made a lot of money from working in the movies but my first love has always been the art. At that time, I made a kind of bread-and-butter living from karate, but my main income came through investments and being able to invest in property. I always had a dream of establishing a dojo like in Japan; surrounded by a nice garden, maybe with a river flowing past. Well, eventually I got that and it was really lovely, but it was very big and attracted all the overheads that large properties attract, so eventually I was able to sell that and create a smaller version that was much better. From the sale of that particular property I became financially secure enough to pursue karate as I wanted to, without worrying too much.

What are your thoughts on the concept of celebrity in karate?

There seems to be a number of instructors these days that might come under this banner. In a way, if someone is able to draw large numbers of people, and they are giving good quality instruction, that’s fine; but I know what you’re saying and generally it’s not good. I have been in that situation where there have been two or three hundred people on the floor and it doesn’t work too well. But in Germany there is a sensei called Ochi [Hideo Och,i 8th Dan JKA, born February 1940], he is a fantastic man, down to earth and just wonderful.

Every year he organizes a huge training camp and he invites about 10 different instructors to hold seminars; not just from Shotokan, but people from other styles too, and from Okinawa also. Now, take a guess at how many people turn up for this? Three or four hundred? That’s what I would have guessed. On the last one there were 1200 karateka. They all stay in the same place and the atmosphere is fantastic because everyone mixes together in the evenings. But during the day the training takes place in about 10 different halls and each one has training for different levels, so it’s good for the students. I enjoy teaching large groups of people from time to time, but I prefer to teach smaller groups, say 30 people or less. I often question if there is any worthwhile karate training going on when the numbers are so large.

What do you think?

In some ways, yes, but in other ways, no. One good thing about it is when you’re practising a kata together and everyone already knows the kata, then the training can go though some small adjustments, by speeding up certain movements here or slowing down there. In that way you can get your message across to a large number of people all at once. But I wouldn’t recommend spending too much time going to one seminar after another in order to learn or improve your karate.

One of the best things about seminars comes from the meetings you have after the training, talking and exchanging ideas, this is very good. Going back to an individual’s progress for a moment, it seems to me that the longer and more deeply people study karate, the less aggressive they become. What role do you think aggression has in karate? Well, you know, you read in the papers every now and then about some guy who has beaten his wife or girlfriend, or turned violent in some other way. Such people don’t usually have a background in martial arts, and what they are doing is displaying what I believe is stored-up anger. Tensions exist in their lives and then perhaps someone close to them says one little thing, pressing the wrong button, and the guy just loses it. He no doubt regrets it afterwards but it’s too late.

Other people are aggressive by nature and want to fight a lot, although not always a proper fight, but they might get angry in the car at other drivers and do stupid things. Anger and being aggressive are two different things. I know from my own experience that whenever I got angry, I also got hurt. Not always physically, you understand, but nevertheless I still ended up being hurt in some way. Mikiyo Yahara took me to a sumo stable or beya. Nakayama Sensei had told him I was interested and so he brought me to watch them training. I was writing reports about Japan for a South African newspaper at the time and sumo was something I was keen to see. They did all their stretching and some were practicing their thrusts on a large post set in the ground. Then they all fought each other, and the juniors fought with the seniors.

One young guy in particular came in for a lot of heavy treatment. They were really pushing him hard to the point where he was exhausted. At that point they just pored water over him to revive him a little bit and carried on. This wasn’t being done aggressively; in fact they were all being quite good humored and encouraging him.

All this was happening directly after the normal two or three hour training session, and I found out later that it was because he was a jonokuchi, a new wrestler. It’s an expression that means ‘this is only the beginning’, but it is also used in sumo to describe the lowest division of wrestlers. No matter what, he had to keep coming and each time he did, they finished him off and down he went. He had a great way of rolling forward onto the ground, and took everything the others dished out to him. But this is what he was expected to do, so he just took it and took it until they decided to stop. Afterwards, Yahara explained to me that he was new to the beya and this was a kind of initiation to test his resolve.

So every day for the first year he would go through this ordeal. I thought this was to instill aggression in to the young guy, but I was wrong. Yahara said, “No, he cannot be aggressive, just come forward, fall down, get up. Keep coming forward — if you face someone like this, it is very hard to stop that kind of opponent.” Aggression may have some place in karate, but not anger, that’s a different thing. In Japan I have found that almost all the top instructors are nice guys, with one or two exceptions. I won’t name [the exceptions] here, but they are just sadistic by nature I think, and would be like that no matter what they were doing in life.

For the majority, training hard, sparring, hitting the makiwara or a bag, is enough to relieve any pent-up aggression and so there’s no need to hit anyone else. Plus, when we think about the dojo kun [creed or maxims] it helps to keep things calm and remind us of what we are trying to achieve. So in the end it’s about achieving harmony. I have a little saying I use sometimes: ‘Control the enemy and restore harmony’. Now, controlling the enemy isn’t always about fighting, it can be done like you said earlier, with just a look or by adopting a certain posture, something like that — a smile perhaps.

The enemy might not even be another person, it can be health related or to do with business, or whatever. The point is this: when an enemy comes into our lives, we have to destroy the threat and restore harmony. This is sometimes very hard so we need to pray and train hard. The thing is to know how to do this: what do we do? It’s very hard sometimes

Stan, can karate be all things to all people, as some profess it can? And if so, should those who teach karate be completely honest about their own abilities before accepting a student?

I believe that no matter what a new student might want from karate, it is up to the sensei to set the new student straight on what is expected of them. But, to some extent, I think karate can be all things to all people — to a point. In the past I was often asked whether or not I used any kind of screening process when accepting new students. It’s a good question, and important too —after all, I don’t think karate should be taught to just anybody.

After some time I have come to think that the nine Kyugrades, from beginner to Blackbelt, act as a kind of screening process. For me this is just a time to show basic kicking and punching, blocks and strikes, a few kata, and how to move. I don’t believe there should be any free-fighting taught at this stage, just basic kumite drills. All this is to give the Kyu-grade student some insight into what karate training is like. So for me, and the student too, this is the screening process. If a student has not given up after two or three years, he has literally passed the ‘screening test’, because the meat of karate starts from Black-belt upwards.

If a student is interested in entering tournaments, then perhaps the instructor can have special classes that deal with tournament training. But this should be extracurricular to the general karate training, not a part of it. I remember our mutual friend Terry O’Neill saying to me once how he envied the standard of our karate in South Africa.

He put it down to the fact we had been isolated from the rest of the world due to our government’s draconian law of apartheid (the separation of people according to their race), which lead to a sporting boycott of South Africa by most of the world. We had been precluded from entering any international tournaments and so we spent our time training. In Europe, they had tournaments almost every weekend, and so people were training to be successful in them, which is not the same thing as general karate training. In a way, our training was similar to Okinawan training, because, in the same way they were deprived of their weapons and so developed a stronger empty-handed way to fight, we were deprived of the sporting competitions and so I believe we developed a very strong approach to our karate training.

This difference was what Terry had noticed. I know you played the trumpet, and I was wondering if the breathing involved in doing so helped with your karate, or perhaps the breathing you employed in your karate helped with playing the trumpet?

No, I was mostly too uptight in my karate for it to help with my trumpet playing! Actually, it will come as no surprise to learn that to be successful with reaching the high notes in trumpet playing, you have to have plenty of air in your lungs and be relaxed. James Morrison, the famous Australian jazz musician, told me this about reaching the higher notes, which are right out there in the stratosphere. You might think you have to be a bit aggressive to reach those really high notes, but no, it’s completely the other way around.

And just like karate, the breath comes from lower down, what we would call the hara [the conceptual Japanese term for the body’s ‘centre’]. So you try to keep the shoulders and upper chest out of it, and stay relaxed. I’m a strong believer that karate is based on a few common principles, not hundreds of techniques. And if we learn, understand, and then absorb these principles, we can make karate work in ways that physical ability alone can never do.

Listening to you speak about breathing only confirms my belief there is a vital and undeniable link between opposites running through everything we do, would you agree?

You said it! That’s the word to use: principle. Whatever we do in karate we first learn according to the kind of training we are doing, but there is the idea of shu-ha-ri (preserve, detach, transcend), where we learn, and this leads on eventually to the expansion of our consciousness. But this only happens when a person takes responsibility. Some don’t, they just follow all the time and end up being led by the nose until they leave karate feeling disillusioned. I remember years ago feeling quite down at one time; my hips were giving me problems and I was letting the pain get the better of me.

Tanaka Sensei was staying [with me] at the time, and one day he said, “Stan, you, one life… now you make!” In other words, he was reminding me I only had only one life and I should not be wasting it feeling sorry for myself, but be focusing on doing the things I wanted to do instead. It was great advice, reminding me to take responsibility for my life and not wait for other people to sort things out for me. Unfortunately, many people teaching karate don’t see it that way; they want people to depend on them. In fact, the last thing they want is for their students to begin thinking for themselves… Yes, but you know what?

People who behave like this have yet to understand karate. They have yet to understand the purpose of leadership in life. If they need people to be dependent on them, if they can’t say to a student, ‘Look, you have reached this level, and now you need to go on through life and make your own way’, then they are not teaching right. It’s like a parent who brings their children up to adulthood and then says they can’t go out at night, can’t climb high mountains, or can’t travel.

Can you imagine that? If this happened to you, Mike, you wouldn’t have grown into a healthy adult. Imagine if your parents had said, ‘Don’t go to Australia, don’t do karate, don’t go to Okinawa’. You wouldn’t be the person you are now. I’m not saying we shouldn’t listen to people when they give us advice, but basically we have to take responsibility for our own lives, good or bad. It’s the same with karate.

Sensei, I’d like to ask you about the kata you have devised. First of all, why did you feel the need to make your own kata, and secondly, how many are there? I have made four kata altogether, but my intention was never to teach them or have them replace the official JKA kata. In my dojo I have a list of all the traditional Shotokan kata and when I practice them, I put a dot next to those I have worked on.

If a few weeks go by and there are no dots next to a particular kata, then I make sure I work on it that week. Now you have to understand, in my private dojo where I do most of my training and teaching, it’s almost like the Okinawan way. Some of the guys have seen me do my kata and have asked if I would teach them. At first I was reluctant to do this, and told them that these are not ‘official’ kata, but they wanted to learn them anyway. So now there are three students whom I have taught the first kata, ‘Bunkai SOS’ (SOS are my initials). We practice this together from time to time. If they show a really keen interest, I think I will teach them the other three kata also, but only if they pester me enough.

You sound very reluctant, but isn’t this exactly how all the kata originated in karate, by someone in China or Okinawa who had a passion for their martial art, putting together what they knew and what they wanted to preserve?

I think it’s only the passage of time that has given kata the mantle of reverence we see today. Surely if they are based on sound fighting principles and strategies, then your kata are every bit as relevant as the ‘official’ kata handed down through the JKA, right? Well, it’s not for me to say whether or not my kata have any standing, but I have been practicing them for a while and over the years they have stood the test of time. I’m beginning to realize they have value; there are moves in them that deal with knife and handgun attacks, necessary in these times. But look, I haven’t told people they have to learn these kata — in fact, just the opposite; I have, by and large, kept them to myself.

But I’m beginning to see that others are getting something from them and so I may well teach these. I have a dozen or so private students who come to my dojo but they are not always there at the same time. Like I said, I think of our training method now as being more like the Okinawan way, so we don’t spend all the time marching up and down in lines. Some of my students are already Black-belt holders in karate, and want to improve their karate in different ways. So I focus on principles that are relevant to all karate, not just Shotokan. My kata reflects this. I have adopted some techniques from Goju-ryu kata, as well as making use of shiko-dachi (straddle-legged stance), which we don’t have in Shotokan, however, I believe it is a very important stance.

Each generation of your family seems to be involved in karate in one way or another and I know your family is a source of great happiness for you. What role does karate play in your family life these days?

Yes, I am now a family man, from being an only child, and they are the source of my greatest joy. I have four daughters and all of them and their families live here in Australia. Many years ago we had a family meeting back in South Africa and we decided we would like to move to Australia, and by some miracle of God we have all been able to make the move. We all love it here. I feel truly blessed that this has been able to come about because I’m not sure what would have happened if we could not all have come over. My daughters did not take up karate to any serious level. One daughter, Debbie, did well as a junior in South Africa but she didn’t pursue karate at a senior level. She is married to [Sensei] Keith Geyer and so karate has remained a big part of her life, and now her children, and some of my grandchildren, are doing very well with their karate. All four of my sons-in-law are fantastic guys, and I consider them as my sons, not just guys who married my daughters.

They are successful in what they do and keep themselves active and fi t. Again, I consider myself really blessed, and continue to learn from all of them, and my wife Judy, as well as my close friends and students. In the next generation on from daughters, I have six grandsons and four granddaughters. One of the girls, Jessica Geyer, won a world title in kata as a child. She is still very active in karate. In fact, all three of Keith’s children are hard trainers in karate and are at Nidan [2nd Dan] and Sandan [3rd Dan] level. Dean, who was a finalist on Australian Idol, is not only a good singer and actor, but a strong karateka too. None of them teach karate as a profession, they all do different things. I also have a 12-year-old grandson, Jethro, who I take to Keith’s dojo for lessons. So it is wonderful for me to be surrounded by my family and to see that karate is playing a positive role in the lives of so many of them.

Stan, is there anything else you’d like to add before we finish our conversation?

Finally I want to say this: even when something bad happens to us, something good can come from it. Paul of the Bible said, “Be happy when you are faced with adversity.” This is something difficult to accept, but I believe this carries power. I see it in my faith and I see it in karate too. Last year I had a bad fall when I was coming down the stairs at home. I damaged my knee very badly and had to have surgery to get it right.

During my rehabilitation I met a physiotherapist, who commented on how fit I was for a person of my age. He asked what I did to stay so fit, so I told him. He had just retired from elite-level cross country skiing and was looking for something to help maintain his fitness and provide him with a similar physical and mental challenge, so he asked if he could start training with me. Now, you might think that this proves my point about something good coming from something bad, but there’s a better story here. The night before I had my fall, I was teaching the Blackbelt class at Sensei Keith’s dojo in Caulfield. This is something I do once a week. I teach the first half of the class and Keith does the second half. During this class I was emphasizing to the students a few important points they needed to cultivate in their karate, the first of these being to develop a good attitude. From adopting a good attitude comes the next point, yoi — awareness.

When we make you we are switched on, right, we become aware and ready for anything. From this heightened state of readiness comes a perception of our target and so we adopt a good position, because from a good position we can do what it is we want to do. This we call kamae, right? So as the class went on I continued to remind the Black-belts of the importance of adopting all these things, not just in their karate, but also in their daily lives. At the end of the class I singled out yoi as the point I really wanted to emphasize. Telling them that being aware of their surroundings was perhaps the most important point of all those I had spoken of. I reinforced the message that there was no point developing such a high level of awareness in the dojo if we neglected to use it outside in our normal lives.

Now here’s the sweet part. The very next morning, having said all that I said to the students the night before, I get up out of bed and walk down the stairs — without yoi and… crash! Look what happened: I damaged my knee so badly it required surgery and I was in a brace for weeks. Even now I am still busy rehabilitating it. So this has been a big lesson for me, a real wake-up-call! [laughing] I think that ‘lesson’ might be a good place to end the interview.

Sensei, thank you very much for your time, your thoughts, and your insight into karate. □

Blitz Magazine Vol 31