WING CHUN vs. HUNG GAR -Henry Araneda

A comparison of Kung Fu systems.

Story by Henry Araneda

Both Wing Chun and Hung Gar are kung fu systems that developed in Southern China. That said, it’s very difficult to write about the history of these martial arts in just a few pages, not only because they took a long and winding path to become what they are today, but because their histories are a mix of sometimes contradicting legends, myths and historical facts that can easily become confused.

There were also many influencing factors at play in the development of the kung fu styles, including religion, philosophy, superstitious beliefs and politics. The legends that document the early development of both Wing Chun and Hung Gar were passed down verbally from master to student, so at times they could be ambiguous due to the fact there was no evidence kept from the time these systems were founded. So, here goes a brief history of Wing Chun and Hung Gar…

THE HISTORY

Both systems allegedly began around 300 years ago after two monks fled the persecution of the Manchurian emperor of China during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). One of them was 22nd-generation Shaolin monk Ye Chen An Zhu from the Northern Shaolin Temple, who, according to historians from Fatshan, China, was the person responsible for teaching Wing Chun to people who became involved with the Peking Opera. The other was monk Gee Seen Sim See, the Abbott from the Southern Shaolin Temple, known today as the person who taught the founder of Hung Gar (Hung Hei Gung) on the Peking Opera Red Boats. This was at a time of oppression for China’s general population. The minority Manchurians ruled the majority Han people with harsh laws and zero tolerance, forcing Chinese men to adopt Manchu customs like the infamous queue (braided pony tail). To prevent the Hans from mounting an armed resistance, they also banned the use of weapons and training in martial arts, but this ultimately backfired and provoked violent resistance. It’s well known that rebel activity flourished in the Red Boat Peking Opera troupes that travelled along the Pearl River in Southern China. This was the perfect environment for anti-Qing rebels to hide from the imperial soldiers, as they became performers, wearing costumes, painting their faces and adopting ‘stage names’, and sailed from town to town. Many secret societies were formed in this environment. After the period of the Red Boats Peking Opera, Hung Gar and Wing Chun took quite different journeys.

On one hand, Wing Chun was passed down to 4th-generation Wing Chun grandmaster Leung Jan and from him it was passed to a select group of students for several generations until Grandmaster Yip (Ip) Man taught it openly in Hong Kong. It has since become the world’s most famous kung fu system, mainly due to Bruce Lee, who was a student of Yip Man. Hung Gar, meanwhile, also became one of China’s most well-known systems because it was taught openly to many people as part of rebel efforts to overthrow the Qing Dynasty. The most famous master in Hung Gar history was 5th-generation Grandmaster Wong Fei Hung (one of the ‘10 Tigers’ of Canton province), the man responsible for shaping the system into what it is today, and the subject of many kung fu movies based on his legendary life.

THE COMPARISON

Both systems predominantly use hand techniques over kicking techniques and most, if not all, kicks are delivered to the opponent’s midsection or lower. Apart from that, however, Hung Gar and Wing Chun are quite different in theory, practice and combat application. Wing Chun works on the centerline theory, utilising the fact that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Everything is based on the shape of a triangle to facilitate simultaneous defence and attack. Leung-style Wing Chun also focuses on the theory of ‘opposite direction’ and utilising various types of speed (see the article ‘Interpreting Wing Chun’ at www. blitzmag.net for a full explanation). In Wing Chun you will only fi nd a handful of forms. There are three empty hand forms — Siu Lim Tao (‘The Way of Little Ideas’), Chum Kiu (Seeking the Bridge), Biu Jee (Thrusting Fingers) — as well as a wooden dummy form, a kicking dummy form and two weapons forms: the Luk Dim Poon Kwan (Six-and-a-half-point Pole) and the Bart Chum Do (Eight-slash Knives form). Each form is used like the English alphabet, where the techniques are performed one at a time like the A-BC, not following a particular fight sequence like in Hung Gar. This way the practitioner has the chance to pick the ‘letters’ and create ‘words’ — that is, fi nd an infinite array of fighting applications. One other very unique training method in Wing Chun is chi-sau or ‘sticky hands’.

With this method the student basically trains touch sensitivity and learns how to cover the area he/she has exposed and exploit the openings created by the opponent’s movement and energy. Hung Gar’s motto is ‘Hard as Iron, Soft as a Thread’. It is based on the concept of an immovable foundation and students are encouraged to block with strong forearm techniques, hoping to hurt and possibly injure opponents’ limbs. This concept is trained via the use of iron rings on our forearms, and forearm-clashing to condition the arms against impact. Hung Gar is mostly known as an ‘external’ kung fu system, but advanced students are introduced to the internal aspects of training, going in to chi kung (or qi gong) internal energy training, which aids health and wellbeing as well as power delivery. In Hung Gar there are a little over 30 forms. The empty-hand forms are divided into four sets, known as the ‘Four Pillars’, which are the foundation of the Hung Gar system. If a student has not learnt all four sets, they cannot be called a true Hung Gar Master. The Four Pillars are: Gung Gee Fook Fu Kuen (Taming the Tiger), Fu Hok Seung Ying Kuen (Tiger and Crane Double Shape), Sup Ying Kuen (10 Pattern Fist) and Tit Sin Kuen (Iron Wire Fist).

In the weapons forms, there are both short-range weapons such as the broadsword and straight sword, and long-range weapons like the long pole, spear, tiger fork, kuan to, and the five and nine-section whips. Hung Gar also has two-man forms, which are divided into two separate groups, empty-hand and weapons. These are just to name a few. The main difference between Wing Chun and Hung Gar is that although they are both very effective martial arts, they each follow different paths in pursuit of excellence. Wing Chun is a system designed for fighting; it will teach the student how to improve his awareness, sensitivity, co-ordination and power through its unique applied fighting method. There are no chi kung training methods or chin na (grappling) methods — at least, not as passed on in my lineage from Grandmaster Yip Man. It’s all about simple, direct intercepting and attacking, covering not blocking, jamming with force, redirecting your opponent’s power and using devastating low kicks. Hung Gar, on the other hand, is an artistic expression of power and employs the combination of the Five Animals and Five Elements training methods to rip muscles, break bones, dislocate joints, etc.

Here is the list of animals together with their main characteristics and equivalent element, according to Hung Gar theory:

• Dragon: Hard and soft simultaneously. It uses sinking power. Its element is Earth.

• Snake: Soft and flexible until it has to attack, then it becomes hard and sharp. Its element is Water.

• Tiger: Fierce and powerful, with strong bones and tendons. Its element is Fire.

• Leopard: Fast, strong and employs momentum. Its element is Gold.

• Crane: Balanced in attack and defence. Its element is Wood.

The sequences shown on these pages show a clear difference between the two systems’ approaches to combat, but each is effective in its own right. □

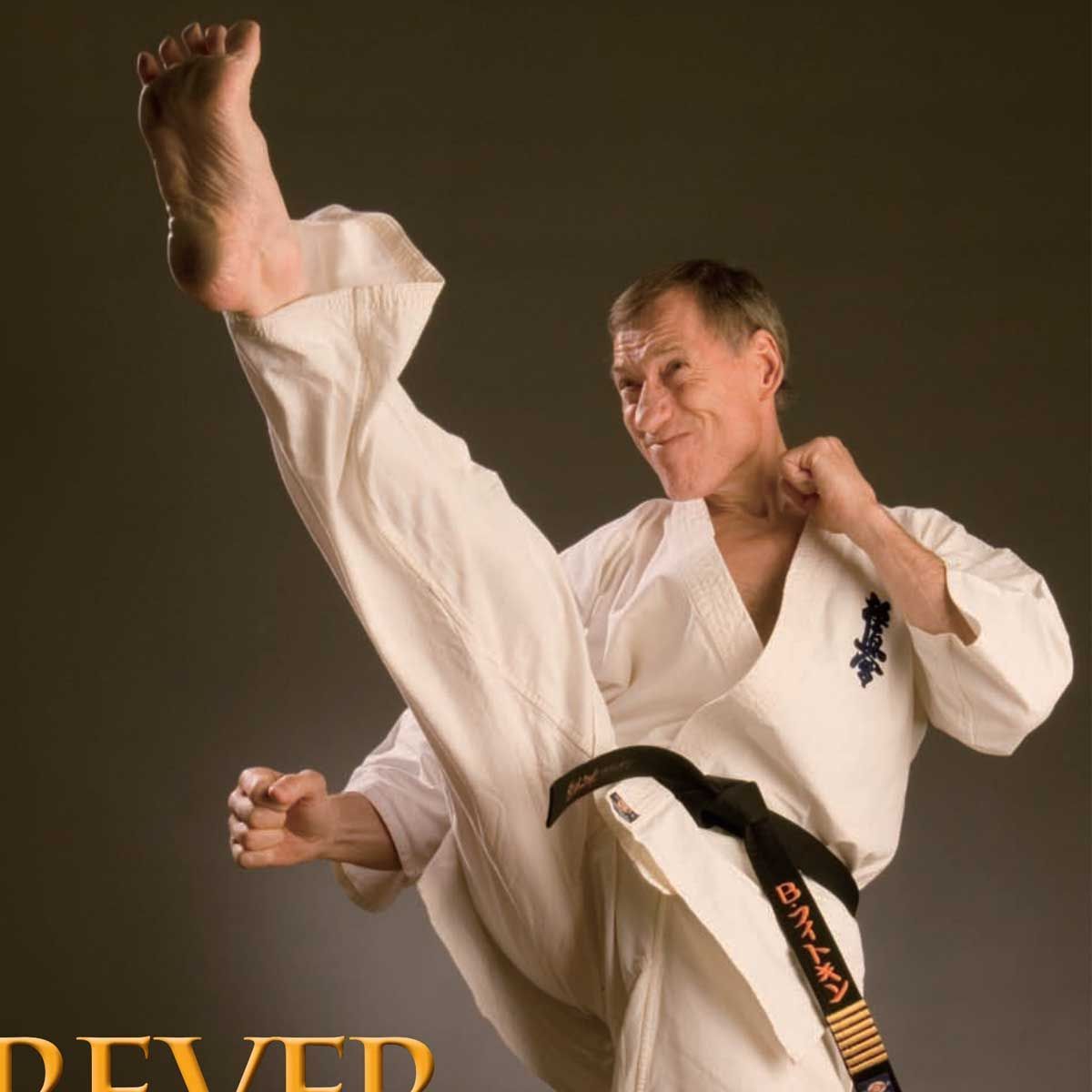

SIFU HENRY ARANEDA

Born in Sydney, Australia, Henry Araneda began his martial arts training at a very young age and achieved an instructor’s level in different styles. During the early 1990s he immigrated to Chile, South America with his family and began training in taekwondo and kung fu for many years, later competing with success at an international level. However, being a Bruce Lee fan, Araneda was always intrigued by Wing Chun theory. There were no Wing Chun schools in Chile, so after some research he found Master Li Hon Ki, based in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Araneda made contact with the master and soon after travelled to Brazil by bus, crossing three countries over 72 hours just to meet the master. He was ultimately accepted by Li Hon Ki as a private student and took many more trips to Brazil to continue his training with Master Li in both Wing Chun and Hung Gar, during which time he stayed at the master’s home for extended periods. Since returning to Australia, Sifu Araneda has travelled extensively to Hong Kong and China to further develop his Wing Chun skills with Sifu Duncan Leung and train at the famous Lam Jo Hung Gar Institute with Grandmaster Lam Chun Sing. He also brought Leung to Melbourne for seminars in 2006 and has travelled with him to teach in Chile.

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, FEBRUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 02