IN THE STEPS OF SAMURAI - Darren Friend

When facing a sword-wielding attacker intent on doing you harm, you can’t rely on heavy leather armour to save your skin — and bones — from a blade that, in deft hands, can easily cut through bamboo thicker than a human arm.

This is why the Samurai not only mastered swordsmanship, but the empty-hand art of aiki-jujitsu, the forbear of modern aikido.

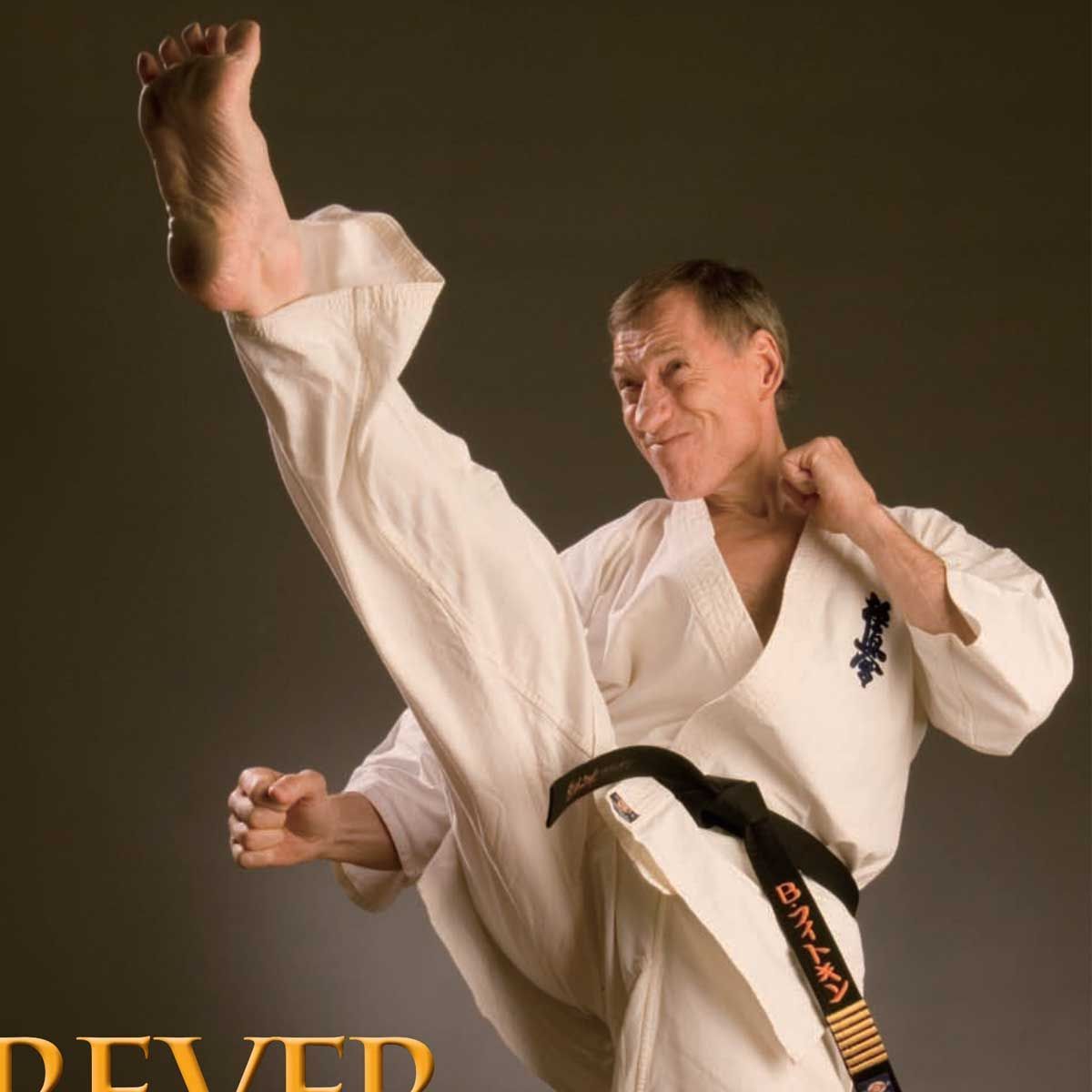

Here, Yoshinkan aikido instructor Darren Friend Sensei reveals the technical principles behind aikido’s evasive footwork, borne of the Samurai’s quest for survival in feudal Japan.

STORY BY DARREN FRIEND

People tend to forget the strategy behind these techniques and their Samurai origins. The art was developed in a time when everyone was armed, so any physical conflict was bound to lead to the drawing of a weapon. Aiki techniques were thus designed to allow the defender to clear off an attacker, draw his weapon and end the fight. This is why aiki footwork is based around the sword; it is all about moving off an attacker’s cutting line while maintaining the ability to draw and cut the attacker down.

Modern aikido still retains links to the Samurai era, which can be seen in the clothing, the hakama (baggy black pants worn by Samurai to hide or disguise their footwork), as well as the many grip-based attacks that, in Samurai times, were aimed to limit one’s ability to draw a weapon in order to defend. In addition to this, aikido still retains the principle of evasion rather than blocking. Aikido’s basic movements are modeled on sword evasion and teach us not to confront an attack directly, but rather to evade and ‘blend’ with the attacker to make the most of their momentum. Moving off an attacker’s centre line makes it easier to unbalance them and derive an advantage that may lead to a technique finishing with a throw or a control. The control aspect is what police and security personnel are attracted to.

Melbourne-based Aikido Shudokan founder and chief instructor Joe Thambu Shihan developed his ‘restraint and removal' course primarily around the controlling aspects of aikido. Kinetic Fighting, as developed for the Australian military by Paul Cale Sensei (currently training at Aikido Yoshinkai NSW), is about clearing off the attacker to allow the footsoldier to draw his weapon and dispatch. Cale Sensei has a broad background in martial arts but acknowledges that key principles of aikido underpin his system. Here, we explore those principles by demonstrating them in various scenarios ranging from the basic to the advanced.

The first sequence shows a simple tai sabaki (body shifting) footwork drill based on the evasion of a sword attack, allowing us to draw and cut with an advantage. As in any martial art, timing is critical. The attacker will commit to his strike with weight placement and just as he does, the defender will slide forward and off the attacker’s line, pivot while drawing his sword, and cut the attacker down. This sword-based movement forms the base for footwork common to several aikido techniques.

In the Yoshinkan system, it also forms the base for one of six kihon dosa or basic movements, which is what students of Yoshinkan Aikido learn first when they begin training. This allows students to model a technique without a partner. Initially, students learn the overall direction, slide forward, step through, turn, etc. As they become proficient, focus turns to maintaining balance and weight disposition, the correct distancing of arms and legs, centre posture and forward focus. Footwork is the key to effective aikido. Most students concentrate on arm placement when they first commence training, but without solid footwork to support us, the techniques fail. It takes time to train the body to adhere to these steps.

To be effective, the footwork must also adhere to the correct weight displacement within each step. The best way to learn this is by feeling the technique as it is executed on you. Yoshinkan aikido students know this and are always trying to be the uke (attacker) for their instructor, so they get the verbal explanation plus a kinaesthetic insight to the technique that’s not available to those merely watching. □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, JANUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 01, page 36