FROM THE WAR TO THE WAY - Pat McKean

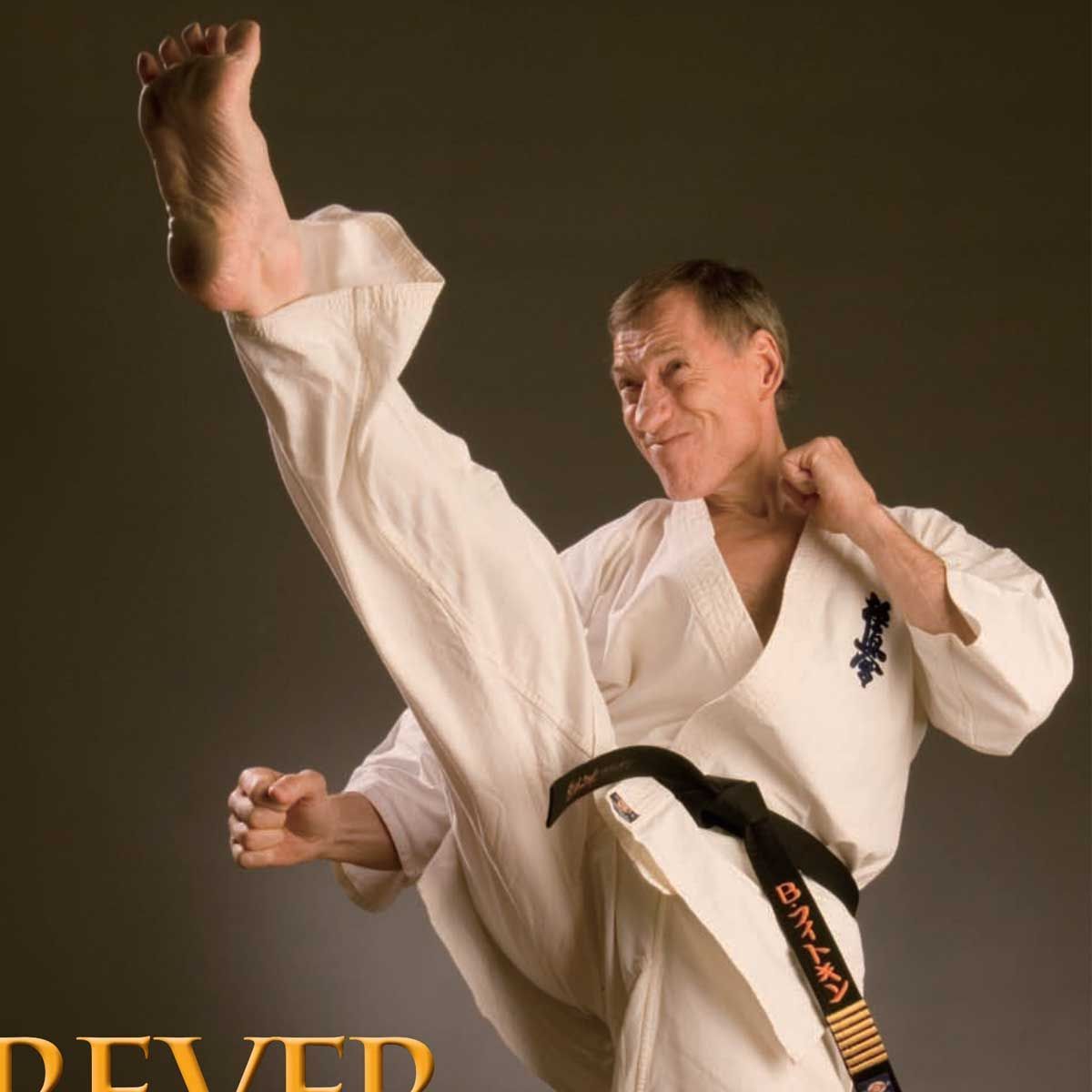

Hanshi Pat McKean is a highly decorated Vietnam veteran — the first to receive his 10th Dan in Shitoryu by Soke Terunari Shiokawa. Undoubtedly one of Australia’s karate pioneers, this exceptional martial artist was also the original instructor of Muay Thai world champ Nathan ‘Carnage’ Corbett.

McKean recently gave Blitz an insight into his martial arts journey, his inspiration, and his philosophies.

STORY BY SYLVIA SCHIAVONI

Hanshi Pat McKean started martial arts when he was knee-high to a grasshopper, at the young age of four, in India where he was born. As the son of an army officer, he spent much of his childhood without his father, who was on the frontline and hardly ever at home. “When I was very young I went to the village and saw these guys training in this ancient style of martial arts called Kalarippayattu, and I made some inquiries,” Hanshi McKean recalls. “In those days there was no real traditional karate in India.”

Kalarippayattu is a southern Indian style of martial art; possibly one of the oldest fighting systems in existence. Seeing the village men training in this ancient method was the catalyst for Hanshi McKean to begin his martial arts journey. “We had servants in that time and they’d take us to the village and we’d do our local form of martial arts, Kalarippayattu, and also Greco-Roman wrestling,” says McKean. He also dabbled in Western boxing, his father’s preferred sport, and recalls fondly how he and his father used to muck about when he was home. “I continued that until I was old enough to go to boarding school, where they had a crude form of Kyokushin karate, which I did more as a hobby,” Hanshi McKean remembers.

Sports were definitely a prominent part of his life throughout his schooling, although martial arts instructors came and went over the years. “All the good instructors of Shotokan and Goju went to America and Europe where there was money to be made,” McKean explains. Over the years, he studied various martial arts styles, including Shotokan karate and Gojo-Ryu, until he went to university. After two years of study, he was given the opportunity to migrate to Australia in 1969 and immediately commenced his study in Filipino martial arts at the South Sydney Junior League Club and kept training until achieving his 4th Degree rank.

But McKean’s life was soon to take a very different turn. He was one of the many young men whose number was called and he was conscripted to fight in the Vietnam War. Strangely, however, McKean says he wasn’t daunted by the prospect of going to war.

“I never gave it a second thought, but naturally everyone was very scared and nervous, as we were only kids,” McKean remembers of the call-up. “It never fazed me.” He attributes this lack of apprehension to his extremely disciplined upbringing as well as his martial arts background. “The martial arts spirit definitely helped me through because once the warrior spirit is embedded in you, you can never lose it,” he reasons. Believing it might make him a target for attack, he never spoke about his training in martial arts while in the army. In 1970, the young McKean was awarded ‘Outstanding Soldier of the Year’ in his training corps at Kapuka. During the war, he sustained some serious injuries and after the war ended, like many soldiers, he also suffered from posttraumatic stress. Still, he returned from Vietnam as a highly decorated veteran and upon his return in 1971 he recommenced training and teaching in Sydney. He was in public service at this time and teaching during lunch hours and after work. “I met and formed an almost brother-like relationship with a senior instructor called Homaioum Alenaddaf and he was instrumental in getting me to form clubs with him,” says McKean. “I have to give him credit for pushing me along.”

He later moved to Dubbo, NSW, where he pioneered martial arts in many Western regions. “I had contact with many different instructors — too many to name — and they all had their schools and I didn’t have a formal school,” the Hanshi says. “When I moved to the country, being a Vietnam soldier, I joined the RSL and started teaching and made a formal club in the RSL and PCYC. Then, from a hobby, it very quickly became a profession.” McKean established approximately 15 dojos around the Western NSW region, going as far as Bourke, Warren, and Narromine. “I even taught the famous cricketer Glenn McGrath for a little while,” he says. “I think he got an Orange-belt with me in Narromine.” In the late 1970s, the ex-soldier was introduced to Hanshi Hisataka from Japan, head of the world Shorinjiryu Kenkokan Karate Federation, who became his mentor and gave him formal training in Shorinjiryu. In fact, it was Hanshi Hisataka who named McKean’s style ‘Kenkokan’ karate.

Over the years, McKean has made numerous trips to Japan to visit Hanshi Hisataka and has trained, refereed, demonstrated, and achieved grades under him. “Shorinjiryu is very Okinawan,” says Hanshi McKean, “The main principles involve punching with the vertical fist, twisting of the body, pivoting of the feet — unlike traditional and modern-day karate, which is punching with a square fist, shoulders square and just rotating of the hips, but no pivoting of the feet. [Kenkokan] is a bit more unique, where you have your shoulders forward, vertical fi sts and the pivoting of both hips and feet; similar to throwing and striking with a baseball, twisting your body completely.” During one of Hanshi McKean’s trips back to India, he helped Hanshi Hisataka establish Koshiki karate, which is not a style but just a system of sparring with head- and body protectors. In fact, McKean was one of the first — together with other senior instructors of Shorinjiryu and other styles around the world — to bring the Koshiki system to Australia from Japan.

Hanshi Hisataka invented the Koshiki system in 1987, a year before he passed away. This system was developed out of a desire to provide “super safe” protective gear for training. “Koshiki has a few meanings: hard-style, safety contact karate,” McKean explains. “If you’ve got a helmet and body armour, it reduces the risk of injury but it actually allows you to feel a strike and to feel what it feels like to be struck, with safety protection. This is important in real-life scenarios because one of the first things that happen, any experienced or inexperienced fighter will tell you, is the first punch basically goes to the head.” When it comes to teaching, Hanshi McKean instills clear principles in his students: discipline, good hygiene, a positive attitude, and good manners. The martial artist runs a very strict dojo and upholds a solid code of ethics. He advocates strictness and fairness but is not overly hard on his students physically, because “it is modern times and students have a multitude of other commitments, like work, study, and family “Every school, it doesn’t matter what martial art – and I say this respectfully – has got to have some principles,” Hanshi McKean says. “Like in a business, you have to have a mission statement. For karate, it’s basically discipline, self-defence, flexibility, being a better person, trying hard, trying to improve, and training consistently.”

The 10th Dan also stresses the importance of being helpful, in particular when it comes to beginners. “You have to be helpful because I believe many instructors forget the mind of a beginner,” he muses. “Everyone has been a beginner and it is important to help those people who are not as physically talented as you. We treat our White-belts with the utmost respect; in fact, we might show them more favouritism than the senior students to encourage them along the path.” In fact, Hanshi McKean believes the word ‘karate’ should be substituted with ‘karate-do’ — do meaning the ‘way’ or ‘path’. “A lot of people think ‘karate’ and not ‘karate-do’ and do is very important in karate,” he says. “Karate is about mind, body, and spirit. The way is never-ending.” Obviously, students begin studying martial arts for many reasons: maybe they have been introduced by a friend, their parents have enrolled them, or they have watched martial arts movies, often from the Bruce Lee era. With any new students, McKean wants to know why they have started and whether they really want to train. Hanshi McKean lets new students know early on that learning martial arts is not just about self-defence or tournaments. “If you’re going to train, you must have a long-term or short-term goal,” he says. “Karate training is to improve yourself in mainly the physical but also the mental and the spiritual, not as in religion but as in the common-law aspect.”

When it comes to the competition side of karate, McKean encourages it but leaves the decision up to the students. “A lot of instructors really encourage, perhaps too much, competition but I just leave it open to my students — although, it’s useful to improve in all aspects.” McKean and his students recently returned from Japan’s biggest Koshiki tournament, joining over 1000 competitors at the 10th All Japan Goju-ryu Karate-do Championships held in Sendai, which was organised by Hanshi Kenjiro Shiba. When it comes to combat, McKean believes that not all people are born to fi ght. They need to possess what he refers to as a physical ‘hardness’ coupled with a mental ‘hardness’. He uses the infamous Nathan ‘Carnage’ Corbett as an example. Hanshi McKean was the first and the only traditional teacher of Corbett and has always considered him a very close friend, not just a student. He recalls taking him to Japan when he was a young boy and to America when he was a young adult. “He was unequivocally versed with physical attributes,” he says. “He just had a fantastic, what we call ‘hardness’, because martial arts is about hard and soft. At the end of the day, when it comes to rugged sports like Muay Thai or full-contact, there is no softness – it’s all hard.” He attributes Carnage’s hardness to his strict traditional martial arts base, which instills discipline and fortitude in his students. “I really think that you have to have both mental hardness as well as physical hardness to fight, and Nathan has both.” So, what are the key ingredients to an all-around great martial artist? “You have got to know yourself and you have to be very honest with yourself and train sincerely,” the 10th Dan master says.

McKean is a great believer in the notion that the type of martial arts you are suited for is dictated by the way you live in your personal day-to-day life. “People who are disciplined in their personal life grow to be successful in their martial arts and in their professional life,” he explains. Due to his serious battle injuries, the Vietnam veteran is obviously restricted physically but that doesn’t mean he can no longer help guide people along their path. He is an inspirational mentor and still attends training a couple of times a week to oversee and mentor his club, UKB Kenkokan, on the Gold Coast. Hanshi McKean has achieved a lot over his martial arts journey.

In 2003, he was inducted into the Australasian Martial Arts Hall of Fame and the World Karate Union Hall of Fame as Queensland’s Instructor of the Year. Most recently he achieved his 10th Dan in Shito-ryu from Soke Terunari Shiokawa. He achieved this for his martial arts expertise, time and effort and his outstanding contribution over the years. Hanshi McKean credits many mentors for inspiring, guiding, and teaching him over the years: Yamaguchi Sensei, Hanshi Tino Ceberano, Frank Nowak, and Kancho Kimura, who have all passed away. In the last decade, Hanshi Shiokawa from Shimonoseki city in Western Japan has been a father figure to McKean, both in karate and iaido [Japanese sword fighting], which Hanshi McKean doesn’t formally teach but practices. Hanshi McKean says his main inspiration for over 25 years has unequivocally been Hanshi Hisataka, whom he says replaced his father, who passed away when he was quite young.

In Australia, McKean’s current mentor is jujitsu and kung fu master Kancho Barry Bradshaw from Melbourne. “Apart from these people being excellent martial artists, they are all decent people and they have all had formal training, which I missed when I was young,” McKean says. Fittingly, Hanshi McKean possesses some of the very attributes he compliments his mentors as having, and more. It is obvious he is an exceptional martial artist, but he also comes across as a decent, open, and humble man. □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, JANUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 01, page 30