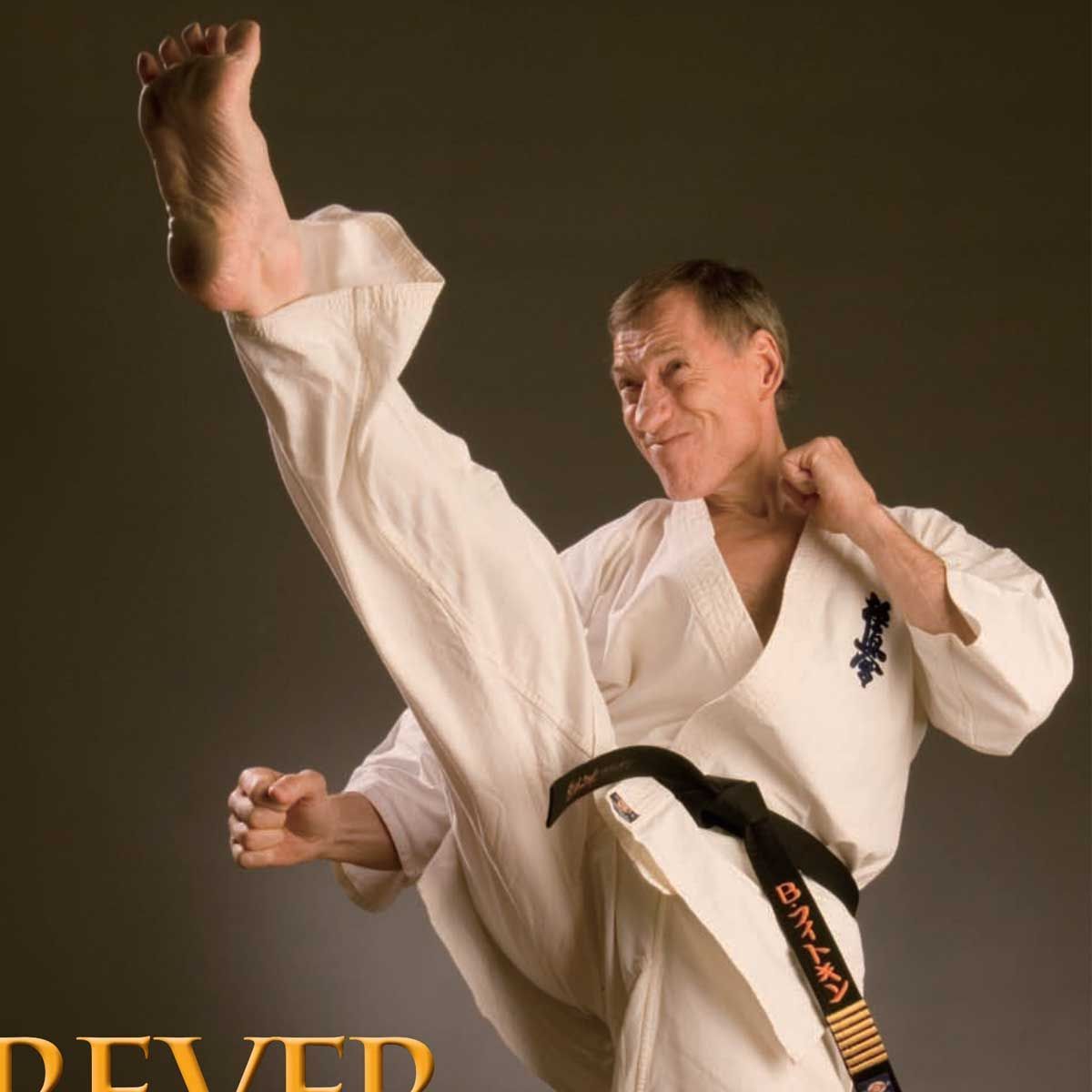

PASSION vs. EXPERIENCE - Graham Kuerschner

THE TACTICAL APPROACH BY GRAHAM KUERSCHNER

Can relying on previous experience stop us improving our skills?

In the last issue, I spoke about what has been called the ‘experience trap’ — that is, a situation where a person’s previous experience actually hinders their ability to learn from their mistakes and further improve. This phenomenon was exposed by two professors at the INSEAD business school in France who conducted a study involving several hundred experienced managers in a computer simulation of a real world project.*

In the process it was noted that many managers ran through the simulation and made errors, and then tried it again after receiving feedback, but still made the same mistakes — despite the fact that many of them were very experienced. Other studies confirmed that this phenomenon was not restricted to managers or even businesses.

Many professionals, including sportspeople, suffered from a similar problem. In an overarching study of this phenomenon (initially from a business perspective), Gary Colvin, the Senior Editor of the prestigious Forbes business magazine, found the same thing. In his book Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else, Colver goes on to describe the principles of ‘deliberate practice’.

This is an activity that’s specifically designed to improve performance, usually with an expert or instructor’s help. It can and has to be repeated a lot; continuous feedback on results is available; it’s highly demanding mentally and it usually turns out to be much fun. Sounds a lot like what we all normally think of as ‘practice’, doesn’t it? Well, not quite. When we say that deliberate practice is ‘designed to improve performance’, the operative word is ‘designed’. Just throwing a hundred punches or kicks against a bag, for example, doesn’t qualify. There is a great body of knowledge in the sports science field as well as in cognitive psychology in general about how we best learn and improve. Our practice must follow those principles.

Most importantly, the elements of performance requiring improvement must very carefully and specifically be identified so that practice that directly focuses on those elements can be designed. This is very clinical and demanding. And while we know that what counts is quality training time, what we mean by ‘quality’ is not really the quality of the technique per se (although that’s quite important).

Rather, it’s firstly the quality of the analysis to identify our specific personal areas of weakness and, secondly, the quality of the methods or drills used to improve the area(s) requiring attention. That generally means an independent experienced coach or instructor to spot those areas and then guide and critique the training. At the very least, it requires some means of objectively observing or measuring our performance. This is very difficult to achieve either solo or in a group or class environment. That presents the third challenge: repetition.

The mental discipline required to undertake high repetitions of the identified skill and maintain the quality of that practice is usually beyond most except the extremely dedicated. As Colvin noted: “A finding that is remarkably consistent across all disciplines is that four or five hours a day [over several sessions] seems to be the upper limit of deliberate practice”.

The observation that such practice is therefore not fun follows from the above. That seems like an obvious and irrelevant fact, but it’s not. It leads us to a core issue: where does the passion — because that’s what’s required — come from to drive ourselves through such a demanding regime of practice and in the process give up many other things in life?

The passion doesn’t accompany us into this world, just like the high level of skill it develops. World-class achievers are driven to achieve but most don’t start out that way, as many people might think. They need to be both pushed and nurtured until the passion reaches the level required to undertake sustained, deliberate practice. And that requires a talented instructor. □

* You can view the INSEAD study at https://knowledge.insead.edu/career/experience-trap Graham Kuerschner is a 44-year veteran of the martial arts and can be contacted through his website at https://www.sdtactics.com.au/

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, JANUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 01, page 104