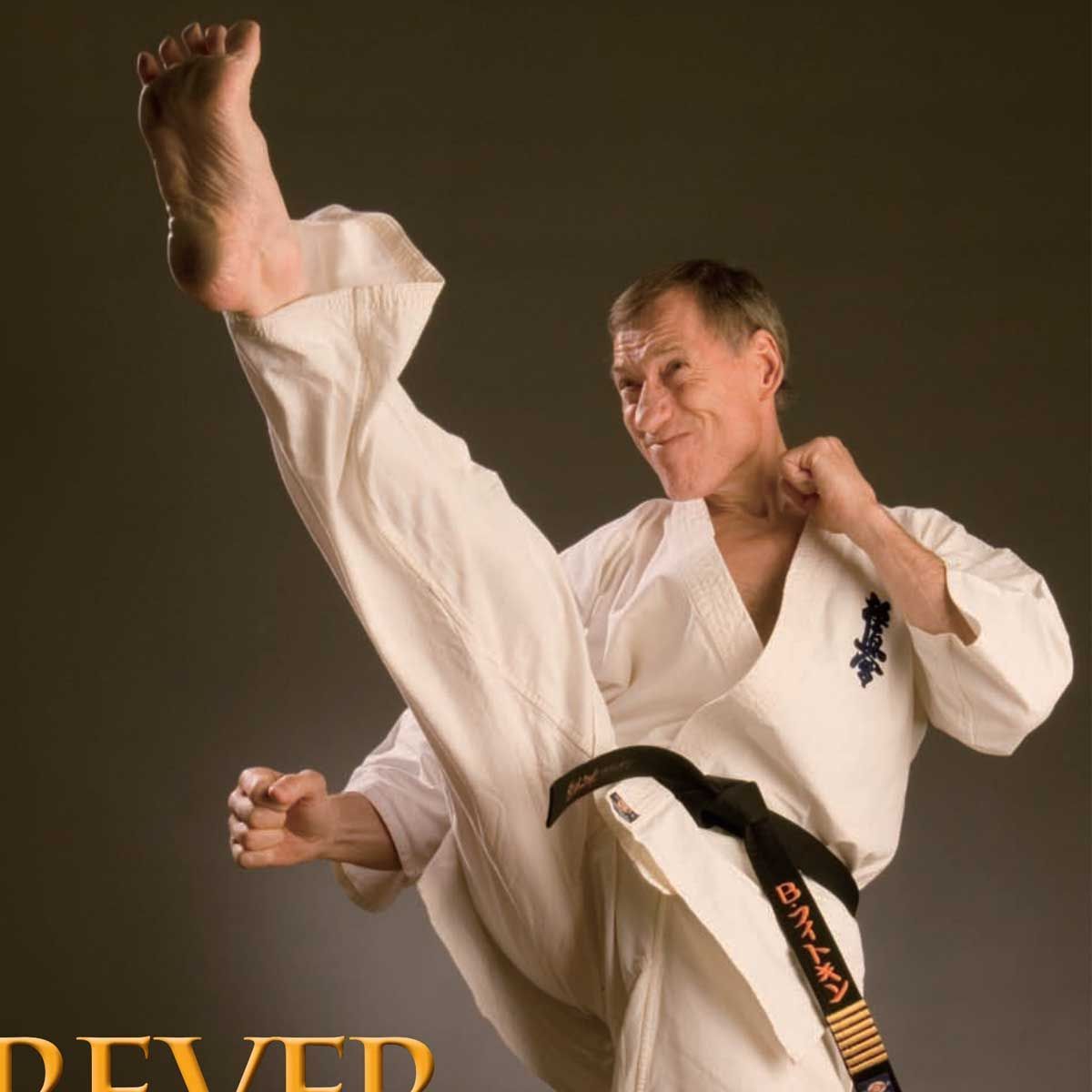

BEST OF BOTH WORLDS - Frank Stranieri

Sensei Frank Stranieri went to Japan to train at the source of aikido — the soft, flowing and highly technical martial art, which has limited striking and aims to use an attacker’s momentum against him.

However, in 10 years there he also took on a very different challenge: Kyokushin, the full-on, full-contact karate style where strength of heart is as important as brutal simplicity of technique.

He also grappled with a style of jujutsu from an old Samurai family and today, back in Australia, has fused his knowledge into a system he calls Kaieden.

You went to train in Kyokushin after several years studying aikido — what aikido rank were you, and how many years’ aikido experience did you have, when you crossed over to ‘the hardest karate’, as it’s known?

When I began Kyokushin I was already graded Nidan [2nd Dan], in aikido, which I was doing for approximately 12 years. As a beginner in Kyokushin, my focus was really training hard and seeing how far I could take it. Aikido took second stage during this time. I suppose there was a burning desire to see where it might go or how well I could do against ranked fighters/instructors, and what I could achieve in this hard style.

Martial artists often start off with a hard style and graduate to a softer style as they get older and more experienced, or they defect from a softer style to a hard style very soon after starting training, when they realise it will take them years before they will be able to use the soft system effectively in self-defence, given its higher level of technical difficulty. What made you instead leave Kyokushin as a teenager, to take up aikido, and later take up Kyokushin again after quite a few years of aikido training?

Initially, although I was progressing in Kyokushin and training with the adults and developing flexibility, agility and power, I was still a 14-yearold boy. I began experiencing problems with my knees and had to stop Kyokushin due to doctor’s advice. Aikido seemed to be the ideal martial art at the time, as it was dynamic, flowing and I had seen a demonstration of Kancho Shioda Gozo, which I thought was something really special — quite amazing. Aikido at the time in the West, in many ways, was unheard of, even among martial artists.

Later, in Japan, there were a number of reasons why I took up Kyokushin karate. By the time I started Kyokushin I felt quite competent with my ability in aikido and my level of achievement. I had already trained in aikido with arguably the best masters in Japan. In some ways I needed a far bigger and greater challenge. The second was that I really missed the competitive factor; getting in there and just training like there was no tomorrow. This provided a hard-contact style of training, which aikido didn’t really have. My own observation was that in Kyokushin people at the hombu were more transparent in a way. It’s is very much black and white: you fight — and you do well, or not. You learned pretty quickly what was required of you.

The final reason was that I got attacked by a gang of crazed guys in a nightclub in Shibuya, Tokyo. There were six against me. I was hit on the head with a steel object and remember seeing blood run down the side of my face. Within seconds we were fighting. I was just throwing guys, blocking kicks, punching, kicking, etc. The fight went from upstairs to downstairs and then outside the nightclub. I just remember the security staff trying to hold me back, while the gang were trying to get the better of me. This was very difficult to comprehend being in this situation in a foreign land. That was the turning point!

Did you find it difficult as an aikidoka to adapt to the Kyokushin way? Or were there similarities between it and aikido that might surprise some people?

Well, personally, no [I didn’t find it difficult] because aikido gives you the ability to move naturally and I would also use techniques that are also common to karate. Kyokushin karate’s footwork is quite natural too. To be good at karate you need to have an adaptable body and mind, by that I mean you need to learn the basics pretty quickly and fuse them into your fighting technique. So yes, in a sense karate is similar to aikido. The Kyokushin Hombu dojo in Ikebukuro was welcoming — in particular, Fukuda Shihan and Ito, Irisawa, Nicholas and Ikeda Sempais.

In Japan when you trained they would always talk about Kyokushin spirit. It was a constant in everyday training. The teachers at Kyokushin would respect students that trained at their optimum level, who did not give up, were diligent, fair and showed respect. From this point of view, the aikido hombu was the same. In Japan there is a spirit of not giving up and continuing in the face of adversity. This is how you are able to judge your own character and how people view and respect you too. I am not talking about arrogance, but a self-belief to achieve all that you can.

As an aikidoka I felt I was able to bridge the gap better and use concepts like irimi [entering] in Kyokushin. However, for the most part there are rules to abide by in karate so you couldn’t use most aiki techniques.

Why did you later move into jujutsu — and did you find this more akin to aikido practice than karate had been?

I was introduced to my next teacher, Aikira Fujii Sensei, who is proficient in karate and jujutsu. He is my father-in-law. According to him, his family were Samurai. Fujii Hikozemon was one of the vassals for Shibata Kenmotsu who was the brother of the famous Samurai Shibata Katsuie, who in turn was the general of Oda Nobunaga. Oda Nobunaga later became the most powerful warlord of Japan in the Sengoku period. It was a natural progression to practise jujutsu for me as aikido has its origins in aikijujutsu/jujutsu.

I preferred the fact that in jujutsu the techniques were more martial. Its primary focus is to disarm an assailant and finish them off pretty quickly. We would train outside in a park near by his house a number of times a week in Kawasaki City. The training was both very demanding and enlightening. I was able to see and experience the origins of most techniques used in aikido today and how they would be applied using jujutsu. The attitude and intent was very different — very martial!

What, in your experience, were the primary differences between the Aikikai and Yoshinkai aikido styles?

Yoshinkai has a systematic and very structured way of teaching aikido, which develops good posture and basics through a series of essential movements practised with or without a partner. Their techniques are taught effectively and have a more martial approach to the art than most other schools of aikido. Aikikai’s approach is, look and research for yourself. Ikkyo/ ikkajo (first pinning technique) in Aikikai can be done in many ways as the standard form.

At the Aikikai Hombu, the Shihans are so different, to a point that they are developing their own style/techniques and philosophies. Really what is happening is that the basics are changing and evolving more so, as is the art too.

What was behind your moving between various arts and teachers in Japan — had you not found what you were looking for, or were you simply trying to get a taste of all the Japanese arts have to offer?

The idea was to see how these arts would work together; their strengths, weaknesses and to really have a better understanding behind movements, body dynamics and martial spirit. The ability to have a better understanding of other styles and their mindset is essential to my development and understanding as a teacher, martial artist and corporate trainer of Kaieden. Knowledge is power in itself!

What was the reason for starting your own system, Kaieden?

On returning to Australia after living in Japan for almost a decade, I spent some years observing the various martial arts and corporate training programs that were out there. And though many were quite effective, I found that they lacked a holistic approach to wellbeing. In this busy, hectic lifestyle of today’s rat race, it’s apparent that people are more and more stressed, less focused and ultimately out of balance.

I felt that a system such as Kaieden, which also is a martial art, helps to restore the balance in one’s life, through blending physical activity with a spiritual, emotional and intellectual focus. It’s about taking care of the whole person and assisting them through a range of circumstances in their everyday and corporate life such as stress control, breathing exercises and tackling aggressive situations when they do occur. This was my primary motivation in developing Kaieden.

Can you briefly tell us about your Kaieden system, and its aims and methods?

The Kaieden system revolves around courses, which are based on concepts and ideals used by the ancient sage to add value and strength to the individual. These courses aim to provide exercises, movements and techniques that help neutralise fears and thus lead to a more fulfilled life.

Leading a fulfilled life has an inverse benefit in work ethic and day-to-day life of individuals. Kaieden leads people to a new level of happiness and achievement by coaching on ways to cope with life’s demands. This is achieved by educating individuals on how to maintain correct focus, posture, improve memory through a series of techniques, thus gaining better retention and ultimately becoming better at what life’s challenges may bring. □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, JANUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 01, page 28