RESPECT vs. WORSHIP

In the martial arts, there is often a fine line between a culture of respect and one of ‘instructor-worship’ within a school or organisation.

How can we avoid crossing this line, and is it even necessary to avoid it?

Pablo Cardenas started training in Wing Chun Kung Fu in 1980 at William Cheung’s academy, Melbourne. Living in Broadmeadows, Cardenas tested and debunked many self-defense beliefs almost on a daily basis. Serving 21 years in the Army refined his training methodologies and the experiences gained nurtured his desire to provide reality- and evidence-based self-defence. This led to establishing the North Queensland Wing Chun Kung Fu Academy (Townsville). A father of six children, Cardenas applies his ADF experiences at his academy and specialises in teaching individuals according to their age, size, gender, ability, or occupation. “This allows the student the flexibility to accommodate attacks accordingly, not with a one-glove-fits-all formula,” he says.

There’s a fine line between a culture of respect and one of ‘instructor-worship’. It is of natural design, to maintain a healthy order of respect. Unfortunately, the human ego can take something good to an unhealthy level. A healthy teacher–student relationship allows mutual respect, not a blind following. Teachers should act in good faith and for the benefit of those who entrust them with their learning.

Why is this important? It allows for students’ personal growth, to make their own informed decisions, not just become clones of their teacher. To demonstrate characteristics espousing instructor-worship creates an unhealthy devotion or indoctrination, akin to ideological control. Do you want to follow blindly or with an open mind? Can you apply critical thinking and respectfully question your instructor? Can you train in more than one school? Can you attend or host seminars of your choosing? Just how much influence does an instructor demand or want? It is a line that instructors should never cross, as an instructor’s conduct can have a profound effect on a student’s development.

Instructors have an ethical responsibility to do the right thing by the student, regardless of personal interest or benefit. Why? Because the student trusts you. As an instructor, you are an authority fi gure and in a position of trust, but your actions will determine if you are a worthy of that trust, and the title. The very strengths of martial arts training (respect, loyalty, etc.) can easily become the weakness that an instructor or organisation may exploit. They are in their element in nurturing ‘instructor-worship’, as this works to their advantage. This is an abuse of power and control.

Ask yourself: could you be — or have you been — exploited or influenced in this way? In turn, instructors should ask themselves, what would be the outcome of my actions and are they in accordance with the code of conduct? When an instructor’s ego derails, it nurtures the instructor-worship syndrome. Instructors know not to cross this line and to ensure students are not being led along the path of blind faith. To do so puts students at risk of emotional, physical or psychological harm. As a student, if you are preached to, then you are robbed of the chance of thinking for yourself, so be mindful of your actions.

Unfortunately, some hide behind the cloak of instructor-worship; an insider may consider this as loyalty, while an outsider looking in may see it for what it is: blind following. Is this a healthy relationship or a scheme for the retention or controlling of students? A martial arts school can inadvertently indoctrinate students with a particular mindset, but we would be disloyal to ourselves if we found a better path, yet, due to this mindset, we disregarded it. Instructors must respect the rights of students and not take advantage of the privilege or power their position affords them.

This influence should be used only for the students’ benefit, not the instructor’s. Instructors are the key to preventing students from instructor-worship. As in any occupation, resourcefulness and thinking for yourself is a strength sought by organisations — why not in the martial arts?

Michael Muleta is a 7th Degree Master Instructor with the International Taekwondo Federation. He is president of United ITF Taekwondo (Australia), a national organisation representing the ITF presided over by Grandmaster Choi Jung Hwa (son of ITF founder General Choi Hong Hi). Internationally, Muleta is the chairman of the ITF Umpire Committee (Oceania region) and chairman of the ITF Expansion Committee (Asia region). A former multiple national champion, national coach, trainer of ITF world champions, head instructor of Thoroughbred Taekwondo (Australia’s Best Overall ITF Club nine times) and with over 20 schools, Muleta is one of Australia’s most highly credentialed taekwondo instructors. Professionally, he is the CEO of Global Fitness Institute, a Government Registered Training Organisation (RTO) specialising in fitness, sports coaching (martial arts), massage and first aid courses for domestic and international students.

In the romanticised folklore surrounding traditional martial arts values, the master instructor commanded respect through his deeds, his abilities and his profound wisdom and knowledge of philosophy and moral culture. He led by example, he was truly respected, educated in life and, more importantly, showed respect and humility to all others. He was spoken about in glowing terms by others who were also highly respected, not just by his own students or followers, or in self-designed propaganda.

The student would do anything for the master and show overt signs of respect because they felt honoured and privileged, not to gain favouritism or payment, nor through a sense of obligation. While there are still a small handful of highly skilled, highly ethical and at the same time humble masters around, a sadder development of the modern martial arts culture is that the instructor has, in many cases, become a person who ‘demands’ respect. This ‘respect me or else’ mentality is ingrained into the doctrine of their schools, where students are forced to show ceremonial forms of respect (outside of the traditional greetings and etiquette) or risk sanctions, demotions or even expulsions. The modern master may demand respect solely due to his martial arts rank or position within a school, more so than his contribution to the betterment of society or his fellow man. Outside of his martial arts school, that ‘respected’ master is often an egotistical, poorly educated and brash business man.

Martial arts is merely the vehicle to gain respect, worship and status that they can’t get anywhere else in the community. Some think respect is gained when the seniors rough up the juniors, believing that fear creates or equals respect. Fear is not a form of respect. That is a caveman mentality of ignorant people. In such environments, the head instructor can become a self-created cult figure, while students become brainwashed into thinking that person is infallible and must be a brilliant exponent, often with little or no true knowledge of their instructor’s history, background, true ability, and reputation among his peers.

These instructors vigorously protect their false status by jealously sheltering their students, for fear that they will be exposed as mere mortals (and often substandard exponents and/or unethical businessmen) and not the demi-gods they pretend to be. Signs that your instructor has developed a culture of instructor-worship are if he:

• Refers to himself as ‘master’, even below 7th Degree (a great martial artist once told me, if you have to call yourself master, you truly are not — master is something other people call you if they deem you deserve it, not just because they have to)

• Makes you put his name on your black belt or uniform

• Tells you ‘his’ certificate has more value than the federation’s certificate

• Rarely puts on a uniform and demonstrates his art

• Doesn’t show respect to lower-ranked students

• Continually defames other martial arts or instructors

• Discourages you from interacting with students/ instructors from other schools

• Charges exorbitant fees and tells you it’s because he’s worth more than others.

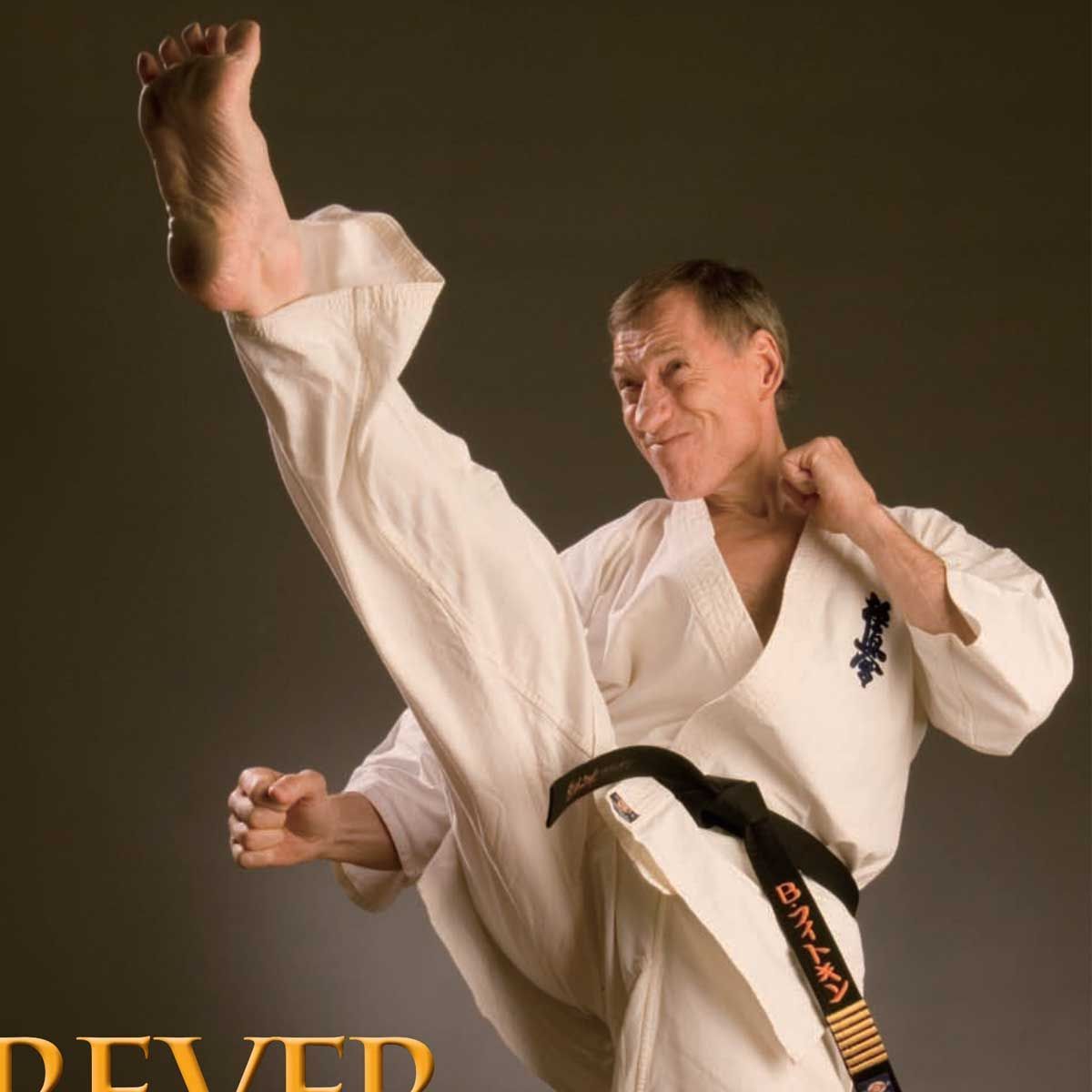

Mike Clarke Sensei, 7th Dan, has been training in karate for 35 years. He travelled to Okinawa for the first time in 1984 to train at the Higaonna dojo and later became a student of Miyazato Eiichi Sensei. He is not available for seminars, although people with the right attitude are welcome to visit his dojo in Launceston, Tasmania. He is a regular writer for Blitz and several other international martial arts magazines, and has published four books on karate.

Although the line between teacher and student may be a fine one, it is nonetheless clear. Celebrity and hero worship have no place in martial arts, and I believe those who engage in such behavior are weak-minded. I cannot speak for other martial arts, but karate is a product of Okinawan culture, and within that culture propriety and good manners are considered the hallmark of a karateka.

On page 48 of his excellent book, The Essence of Okinawan Karate-do, the late karate master Nagamine Shoshin wrote; “When we pursue karatedo, we try to learn the theory and its application from our predecessors and senior karate men with respect and courtesy. On their part, they teach with due regard and consideration, yet with strictness. We must respect this sort of mutualism in which an open-minded relationship between senior and junior karate men is observed.” When individuals who teach karate allow their followers to address them as anything other than ‘sensei’ (teacher), they are pandering to their own egos and displaying a complete lack of understanding of budo. Titles such as ‘shihan’ are so over-used in Australia as to make those who use it seem childish, and slightly ridiculous, in the eyes of those who understand the correct etiquette and protocols associated with such titles.

Responsibility for the misuse of titles, poor etiquette and bad discipline among students clearly lies with the person occupying the role of teacher. It is their responsibility to properly educate those who pay them for instruction. People wishing to understand what karate is should remember they are obliged to walk their own path. Karate is about learning to make your karate work for you. Teaching is only a matter of showing what is possible; learning is making it possible for yourself. No one, not even your sensei, need be addressed in any other way. Respect goes both ways, and only the immature abuse it. When problems surrounding the abuse of power arise it is perhaps convenient to blame the instructor, but remember, people treat us the way we let them, so if your teacher thinks he’s a god, I would say it’s your fault for not pointing out his error. Budo karate is about accepting responsibility for your words, your choices and your actions.

The correct etiquette and methods of interacting with each other in karate are found in, and stem from, Okinawan culture, not Japanese militarism. Overt displays of bowing and saying ‘Ous!’ may have played a role in the evolution of Japanese karate for the Japanese of the day, but its use has long since slipped from relevance. We can avoid becoming mindless followers — or, to the other extreme, becoming overly familiar — by being aware of our own behaviour.

A teacher needs to be mindful of their role, which is not one of ownership in relation to the student, while the student should treat their teacher with respect, while avoiding the development of a ‘fan’ mentality. Students are there to learn and eventually make their own way with karate. Those martial arts teachers who demand loyalty from their followers are, in my experience, often the very people who are least deserving of it. □

Blitz Martial Arts Magazine, JANUARY 2010 VOL. 24 ISSUE 01, page 22